NAIDOC WEEK 2021

Kellehers Australia always yearns for the significance of Aboriginal cultural heritage to go beyond archaeological relics and include Indigenous stories, songs and dances. The heritage of a living culture deeply rooted in oral traditions from antiquity, lives alongside a vibrant contemporary lifestyle of mobile phones and Facebook pages. Whilst this living culture in no way disparages the wonderful work of archaeologists, and the archaeological focus might be called ‘stones and bones’, where buried relics, artefacts and objects can imply a dead culture.

Victoria’s 2016 amendments to the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 recognised what is called intangible heritage. They introduced a system for recording intangible heritage, including songs and stories, on the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Register, and made it “an offence to use registered intangible heritage for commercial purposes without consent of the relevant registered owner.”[1]

Caselaw concerning the important intangible heritage provisions may be evolving. Aunty Joy Murphy tells stories of her rich ‘intangible’ heritage in her award-winning books[2]. Watch this space into the future, as Australia moves strongly toward recognition of its wondrous living Aboriginal heritage, its stories and songs[3]. Listening to Indigenous stories ensures that all Australians are clearer in the shared task of Healing Country.

The cases considered in today’s NewsFlash both concern ‘stones and bones’. However, through them, Indigenous Australians give voice to the stories behind barely visible ancient earth mounds and travelling paths recognised via archaeological work.

…

Image 1: Riddells Road Earth Ring[4]

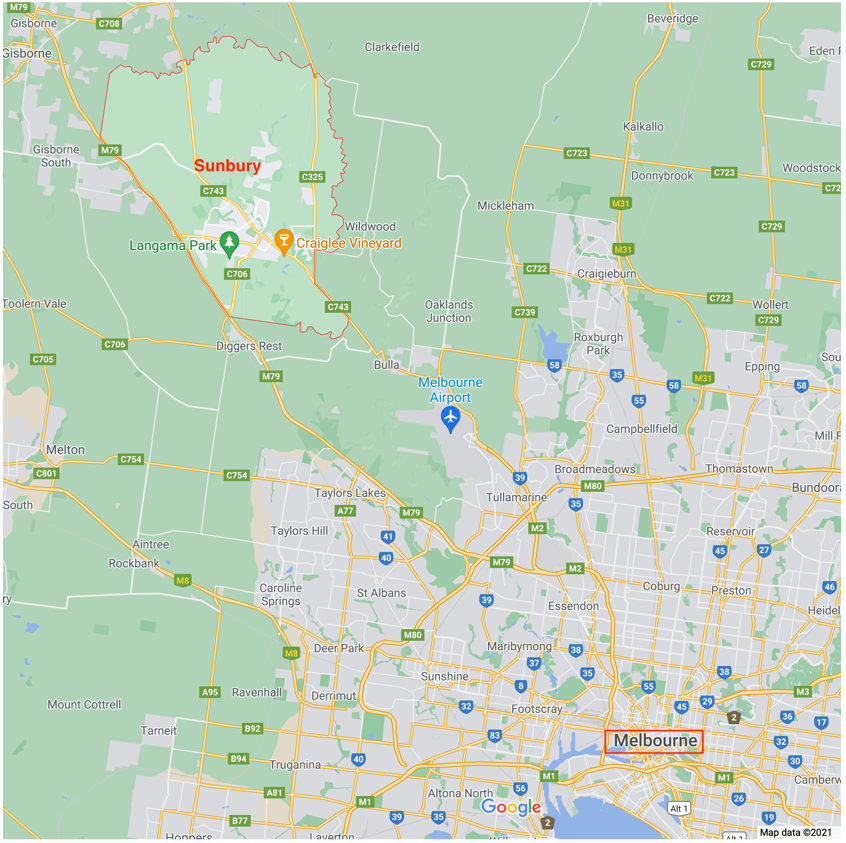

The Sunbury Rings are ancient earthwork formations at Sunbury, a satellite town of Naarm (Melbourne), approx. 40km from its CBD.

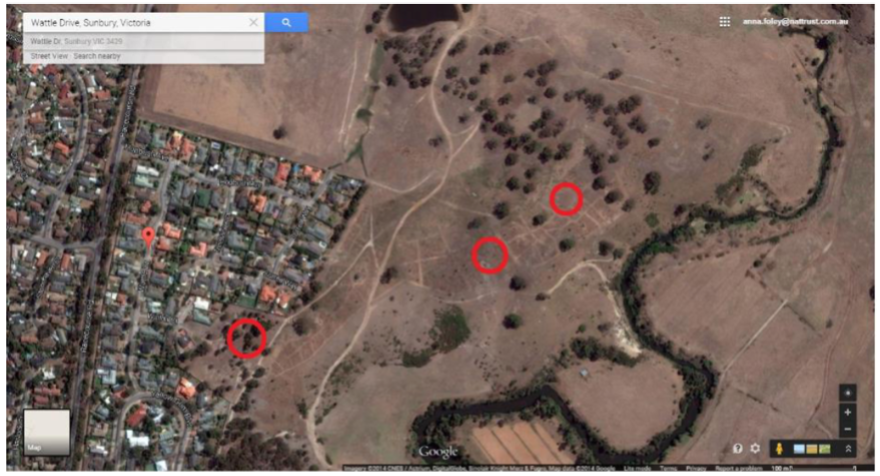

Image 2: Aerial Map of three Sunbury Rings[5]

The Sunbury Rings are located on elevated land within a curve of Jackson’s Creek. Man-made, they date back at least 1,000 years. Most Melbournians would not know that we have our own Stonehenge in the city fringe.

Also called the Wurundjeri Earth Rings, these Rings are said to have been created by the “continual scraping back of earth and grass from the circles centre.”[6] The ring formations include ‘large stoned and heaped soil’[7], with each ring generally around 10 meters in diameter.

There are five rings, with the first recorded in the late 1970s and the last in the 1990s.

The exact purpose or use of these Rings is, at present, not publicly known. Wurundjeri Elder, Dave Wandin says:

“We believe that they were used for marriage ceremonies where men and women would get prepared separately.”[8]

The Wurundjeri are revegetating the land occupied by the Rings to restore native grasses and plants.

Image 3: Google Map of Sunbury[9]

Images: Revegetating of land by the Wurundjeri Tribe Council[10]

In 2015, VCAT considered the Rings.[11] The land on which they exist was within an area proposed for residential development by Canterbury Hills Pty Ltd. The Hume Planning Scheme[12] required the development plan to ‘show, where appropriate … sites of … heritage significance’. VCAT confirmed that ‘heritage significance’ includes sites of Aboriginal cultural heritage significance.

A report by Canterbury Hills’ cultural consultant identified areas of cultural significance, including one of the Rings[13] and four sites Aboriginal archaeological sites recorded under the Archaeological and Aboriginal Relics Preservation Act 1972 (Archeology Act).” [14]

The Wurundjeri Tribe Land & Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Inc (Wurundjeri) spoke for the Rings:

“[Sunbury Ring 4 is] one of the most important Indigenous cultural landscapes in [Victoria]”[15]

“The complex of five ceremonial earthen rings (of which Sunbury Ring 4 is part) remains an important spiritual place for contemporary Wurundjeri people.”[16]

Hume City Council argued that Canterbury Hills’ final development plan should not be approved until approval of the Cultural Heritage Management Plan (CHMP). Canterbury Hills claimed that[17] the estate had been surveyed for cultural heritage in 1984, 1999, 2001 and 2004 and that it was is unlikely that additional cultural heritage would be found. It told VCAT that the estate had been planned in consultation with the Wurundjeri and arrangements existed with them to monitor construction of each stage for the discovery of any additional cultural heritage. The Framework Plan, it said, incorporated the Sunbury Ring 4 into the estate in a manner that met Wurundjeri requirements.

VCAT accepted the developer’s argument. It considered that Sunbury Ring 4 was the most significant known site on the estate but was not in the first seven stages of the development, or in a stage that would closely follow the seven stages. For this reason, it considered there was sufficient time to finalise the CHMP before a permit was granted for any stage affecting Sunbury Ring 4.

…

The Wurund’jeri were involved in an earlier 2005 case, that concerned adjoining Country of the Bunurong People, but for whom they were appointed as the relevant People under the Archaeology Act.

Mt Shamrock is atop a ridge between the Toomuc and Deep Creek valleys just north of Pakenham, a town ~40km east of Melbourne’s CBD. It lies in Bunurong Country.

Mr Steve Compton, on behalf of the Bunurong People, spoke for his Country before a Ministerial Panel considering a proposed quarry extension.

Whitefella law had created complexity. The neighbouring Wurundjeri People were listed as the local Aboriginal community for the area under the Archaeology Act and it was they whose ‘Consent to Disturb’ would be required – not the Bunurong.

The Bunurong were not recognized. The Panel noted that legislative boundaries under the Archaeology Act were not necessarily accurate and were at that time under review.

Mr Compton explained the situation, a situation very common among Aboriginal Peoples throughout Australia in their inter-relationships concerning Country.

‘There was likely to have been an arrangement for shared use of the Toomuc Valley area. … (T)he Toomuc Valley has long been recognized as a track used by Indigenous peoples as it provides a connection between the Dandenong Ranges and the sea.’

Image: Toomuc Creek[18]

The Wurundjeri had made no submission before the Panel. However, the Panel wrote to the Wurundjeri and, in due course, the Wurundjeri’s acting CEO addressed the Panel, confirming the Bunurong’s long connection with the subject site.

The quarry proponent engaged a consultant who produced the usual archaeological survey. Subsequently, a 1989 survey came to light, with Ms L Smith reporting that ‘all creeks within the area, including Toomuc Creek, were potential locations for archaeological sites. Ms Smith developed a site prediction more for archaeological sites. The proponent’s consultant concluded that ‘Aboriginal people carried out a range of activities in the area, including travel between coastal region and Dandenong Ranges, as a lookout location and for the quarrying of stone for tools and preparation of food. She suggested that environmental factors such as access to spring water, plant food and stone resources could have influenced Indigenous movements in this region.

Mr Compton outlined that the subject site is a most desirable location for a lookout, with both Port Phillip and Westernport bays being visible. The Toomuc Creek is the last reasonably un-developed watercourse of significance in the area and it was an area of retreat during extreme cold and periods of drought. Springs would have been flowing for millions of years. He told the Panel that the Bunurong are keen to pursue ways in which their Indigenous heritage in the Toomuc Valley can be preserved and interested.

The Panel noted that neither Mr Compton nor the Wurundjeri was able to advise it on ceremonial places. The Panel appeared to be searching for some particularly sacred or spiritually significant element.

By contrast, Mr Compton told the Panel that:

‘he was arguing for the ‘integrity of the valley’ rather than the ‘integrity of individual sites’.

…

Kellehers has recently been involved in several cases concerning the Birrarung (Yarra River).

Again, the search for Indigenous cultural heritage and the contents of a typical acceptable CHMP invariably focus on archaeological and artefact/object location, along with Indigenous ‘clearance’ for works and development. The stories of the river and the Wurund’jeri and Bunurong, are routinely omitted. How do we redress this enormous silence?

Image: Aboriginal Elder of the Wurund’jeri people Aunty Joy Murphy[19]

Elder, Dr Joy Murphy’s voice rings clear:

“We are the gatherers, and language is an important part of culture still to be gathered.”[20]

KELLEHERS AUSTRALIA

6 July 2021

[1] ‘Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council’, Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Register – intangible heritage (Web page) <https://www.aboriginalheritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/taking-care-culture-discussion-paper/aboriginal-cultural-heritage-register-intangible-heritage>.

[2] Murphy, Aunty Joy and Lisa Kennedy, 2016, Welcome to Country, Black Dog Books, Newtown, NSW – shortlisted for NSW Premier’s Literary Awards and NSW Premier’s History Awards 2017 and winner, Environment Award for Children’s Literature, The Wilderness Society. Murphy, Aunty Joy and Andrew Kelly, Wilam: A Birrurung Story, 2019, Black Dog Books, Newtown, NSW – shortlisted 2020 Childrens’ Book of the Year Award.

[3] Kellehers Australia actively supports the Melbourne Writers’ Festival program for Indigenous writers.

[4] By Gary Vines – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17404643.

[5] ‘Classification Report June 2015: Sunbury Rings Cultural Landscape’, National Trust of Australia (Vic) (Web) <chrome-extension://oemmndcbldboiebfnladdacbdfmadadm/https://www.trustadvocate.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/SRCL-Classification-Report-June-2015.pdf>.

[6] ‘Wurundjeri Council’, Management of Wurundjeri Properties & Significant Places (Web page) <https://www.wurundjeri.com.au/services/natural-resource-management/management-of-wurundjeri-properties-significant-places/>.

[7] Oliver Lees, ‘Rare link to Indigenous history’, Star Weekly, Sunbury and Macedon Ranges (Web page) <https://sunburymacedonranges.starweekly.com.au/news/rare-link-to-indigenous-history/>.

[8] Oliver Lees, ‘Rare link to Indigenous history’, Star Weekly, Sunbury and Macedon Ranges (Web page) <https://sunburymacedonranges.starweekly.com.au/news/rare-link-to-indigenous-history/>.

[9] Google Maps 2021, available through: https://goo.gl/maps/RyMi6muurgV7YNBg6 [accessed July 2021].

[10] ‘Wurundjerie Earth Rings’, Historical RagBag, May 21 2018 (web) https://historicalragbag.com/2018/05/21/wurundjeri-rings/>.

[11] Canterbury Hills Pty Ltd v Hume City Council [2015] VCAT 80.

[12] Hume Planning Scheme (cl 43.04-3 schd 7 cl 2.0).

[13] Canterbury Hills Pty Ltd v Hume City Council [2015] VCAT 80 [21].

[14]This Act was repealed on 28 May 2007 by s 195 of the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006.

[15] Canterbury Hills Pty Ltd v Hume City Council [2015] VCAT 80 [27].

[16] Canterbury Hills Pty Ltd v Hume City Council [2015] VCAT 80 [27].

[17] Canterbury Hills Pty Ltd v Hume City Council [2015] VCAT 80 [29].

[18] ‘Toomuc Creek – Pakenham Walk’, Upper Beaconsfield Community Centre [accessed 6 July 2021] https://www.ubcc.org.au/post/toomuc-creek-walk.

[19] KeynoteworthyAU, ‘The significance of Welcome To Country: why every event should have one’ [accessed 6 July 2021] <https://keynoteworthy.com.au/the-significance-of-welcome-to-country-why-every-event-should-have-one/>.

[20] ‘In Them We Trust’, Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin interviewed by Tabitha Leane, September 2020 < chrome-extension://oemmndcbldboiebfnladdacbdfmadadm/https://koorieheritagetrust.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/26.-Essay-Aunty-Joy-Murphy.pdf>.

Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation

This fact sheet is intended only to provide a summary and general overview on matters of interest. It does not constitute legal advice. You should always seek legal and other professional advice which takes account of your individual circumstances.

Leave a Reply