The untold stories of women whose experiences’ inform our shared future.

Taking further yesterday’s story of the Hon Linda Burney MP and her non-Indigenous mother, we delve today into the rarely told stories of non-Indigenous women who found love in Aboriginal cultures.[i] There is much to tell. It is important to create a shared understanding[ii].

Academics Professors Victoria Haskins and John Maynard draw on Maynard’s Aboriginal heritage as well as western documentary and oral history to examine the complexity of these relationships and reflect that:

‘Any study of sex and love across racial boundaries … (is)… a revelation of devotion, fear, triumph and pain, as well as of broader cultural and gender issues, legal and political struggles.[iii]’

Non-Indigenous women who took the step over the barrier, faced both pity and a desire to rescue them mingled with revulsion, abhorrence and fear. They were often excluded by their own communities and may not always have been fully accepted by their husband’s People[iv].

Early Colony

From the beginning of colonial settlement, as Lieutenant David Collin deputy judge advocate with the First Fleet, asserted:

‘(N)one of our women had connection with Aboriginal men…[v]’

Yet early colonial male observers noted the attentions of Bungaree, a local Aborigine, to white ladies at dinner. They were certain that Bungaree had no chance of taking things further – and this seemed to enhance British masculine superiority in the fragile early settlement[vi].

Reports in 1790 of ‘a white woman living with the natives of Newcastle district’ met with horror. Again, Collins proffered:

‘(H)umanity shuddered at the idea of purchasing it (freedom) at so dear a price[vii].’

A rescue party with instructions to ‘bring her away unless she preferred the life she now led’, failed to find her. Authorities concluded that the escaping convict woman would come to regret her foolhardiness. The white men who controlled settlement could not envisage that a white woman would willingly make her body available to an Indigenous man.

Damsel In Distress Myth

The ‘white-maiden-rescued-by- strong-brave-white-hero’ was a staple melodrama of frontier expansion and a powerful motif in the face of colonial instability and vulnerability. Key to the captivity narrative is an imagined innate delicacy of white women that was vastly different from the reality of their lives[viii].

“In those days most of the females were hardened and indifferent to what fate had in store for them, that they were more like men and it was a common occurrance (sic) for stockmen to exchange their wives with one another or sell them for a pound of tobacco or a keg of rum…”

Despite the gritty reality of the lives of settler women, the ‘damsel in distress’ fantasies obsess with naked blackened bodies that must be transformed back again to attractive female whiteness[ix]. The search for a wild white woman also justified gathering useful information concerning the geography of the country [x] and suited an expansionist aggression. In some instances, it drove gangs of vigilante settlers to frenzies of genocidal violence[xi].

No story of white woman rescue would be complete without mentioning Eliza Fraser. Following a shipwreck in May 1836, Eliza lived with her Aboriginal rescuers, the Butchulla (Badtjulla) People[xii]. Her subsequent autobiography[xiii] shows that she considered herself naturally superior to the Aboriginals, whom she found ‘extremely filthy’. She felt herself a ‘slave to slaves’. Upon return, although shamed and judged to be a fraud and a liar, her claims of mistreatment led to massacre and dispossession for the Butchulla. Nevertheless, a negative ‘damsel in distress’ narrative continues to fascinate[xiv] with Patrick White’s book A Fringe of Leaves[xv], Michael Ondaatje’s long poem The Man with Seven Toes[xvi]‘, artist Sidney Nolan’s many images of her and, in 1976, Tim Burstall’s film Eliza Fraser starring Susannah York.

As the frontier moved, the fantasies relocated. For example, in the 1920s at the Northern Territory frontier, a US film showed a so-called captive white woman waving goodbye to would-be rescuers with her Aboriginal husband and son beside her. Again, after a failed rescue party, the authorities concluded that either she was mentally deranged or that Aboriginal men and/or an unscrupulous American were lying[xvii].

Despite the oft-told ‘damsel in distress’ myth, many positive stories abound. We now explore a handful of these.

The 1800s

Daughter of Benerembah Station Owner

An Aboriginal version of massacres on Wiradjuri country in the 1830s was told by Ossie Ingram in 1990 of one Aboriginal massacre survivor swimming down the Murrumbidgee River and ending up at Benerembah Station, not far south of Whitton, Linda Burney’s hometown. He collapsed on the riverbank where the Station owner’s daughter found him. ‘She cared for him until he recovered, fell in love with him; and ended up marrying this Koori man’[xviii].

Barbara Thompson, née Crawford[xix]

Barbara Thompson was 16 when she eloped to Moreton Bay with her then de facto husband. Shipwrecked whilst sailing off Cape York in the 1840s, her husband died, but she was rescued by Boroto, a member of the Kaurareg People from Morolug (Prince of Wales Island) in the Torres Strait. The Kaurareg People adopted her as the returned granddaughter of a deceased Elder. For five years, she lived happily and well with the Kaurareg people, married a Kaurareg Elder and likely became mother to his child(ren). She learnt language, but found some cultural rules strange, e.g. being unable to speak to her father-in-law.

Even today, her Wikipedia entry refers to her ‘rescue’ by the crew of the ship Rattlesnake[xx]. However, there is no doubt that her choice to return was personal, made slowly over time (i.e. not on the first visit by the Rattlesnake). To the deep regret of her Kaurareg family, her decision in 1849 to return is recorded simply, as ‘I am a Christian’[xxi]. Barbara’s later life goes quiet as likely required in ‘civilised’ society, but it is believed she married at least once and died in 1912 aged 84.

R’s Wife

Often what little legal rights woman had at this time were lost or overlooked. For example, in the late 1800s in South Australia, a woman refusing to live on a mission because she was not Aboriginal was cast by Police as dominating him:

‘I fancy that R— is always completely under the influence of his wife.[xxii]’

George Muckray’s Wife

Also married in the late 1800s, the widow of Aboriginal, George Muckray, was not entitled to take up his Aboriginal lease after he died in the 1920s although, as she argued, she had ‘discharged her duty to the state in rearing up into very useful citizens her 12 children’[xxiii]. She had no entitlement to the special land grants available to Aboriginal women who married white men.

Eva Rankine, née Mugg[xxiv]

Eva Mugg was the European daughter of a bootmaker who lived in the late 1800s at Raukkan (Port Macleay) on the southern east shore of Lake Alexandrina on the south coast of South Australia, Her father taught the boot trade to George Rankine, a Ngarrindjeri man. The South Australian chief protector of Aboriginals, somewhat paternalistically recorded, in support of George’s desire to establish his own business, that Eva was ‘a highly respected white women’ who had ‘helped to raise Rankine far above the ordinary half-caste Aboriginal’. They established a successful bootmaking venture, conducted in a shop attached to the home in which they brought up their family, where they lived happily for many years. After their marriage, Eva and George kept away from the mission and drew no help from it. According to her daughter, there was no need to regulate mixed marriages as ‘people made the laws with their attitudes’.

Ethel Governor, née Page

A pregnant working-class sixteen-year-old Ethel Page married Jimmy Governor at Gulgong in 1898. Accounts refer to Ethel’s ‘incomprehensible failure’ to find ‘anything extraordinary in having married a blackfellow’. Ethel was humiliated by other white women, with her baby criticized, laughed at and made fun of while they minded the child for her. She had two children. Blame was even extended to Ethel’s mother:

‘One naturally wonders what manner of woman the mother was who insisted on uniting her daughter for life to a low-bred aboriginal’[xxv].

Ethel’s story is intertwined with a murderous rampage by her husband that resulted in his being hanged. His story, told by male writers Thomas Kenneally in The Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith[xxvi] and Frank Clune in Jimmy Governor: The True Story[xxvii], is critiqued by Indigenous writer, Larissa Behrendt, who described Kenneally’s vision of Ethel as ‘triply fallen, for piling black marriage on white conception on black fornication’[xxviii].

In the year Jimmy was executed, Ethel remarried another Aboriginal man to whom she bore another eight children[xxix].

20th Century

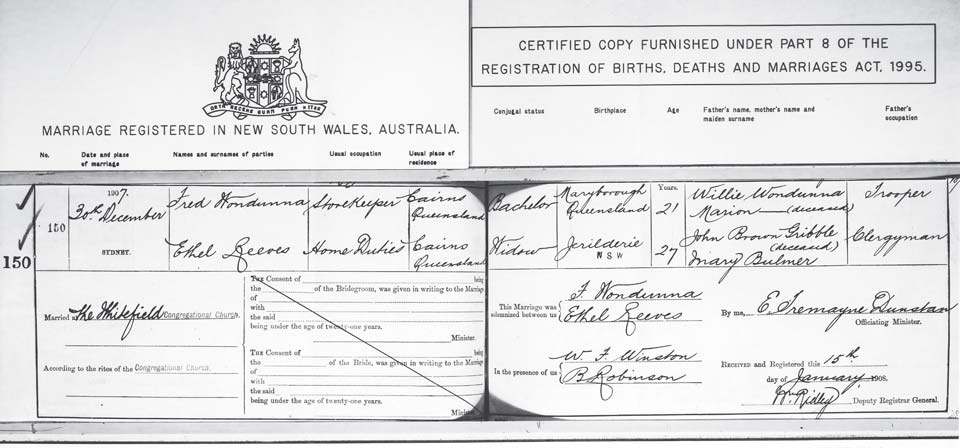

Ethel Gribble

In the early 20th century, Ethel Gribble’s romance with Fred Woondunna at Fraser Island was regarded as unsuitable. She was a respectable middle-class missionary ‘nudging spinsterhood’. With this romance, she was promptly married to a close friend of her missionary brother. However, when the husband died, Ethel’s affair with Fred rekindled and, after she became pregnant, she sought sanction to their marriage. Her brother decided that Ethel had suffered a mental breakdown, urged her to hide her pregnancy, have the child adopted and ‘forget her foolish infatuation’. He sent her to Sydney, where Fred followed, and they were married.[xxx]

New South Wales Registry of Births, Deaths, and Marriages.

Rebecca Forbes née Castledine

Rebecca Castledine married Adnyamathanha man, Jack Forbes, on 17 January 1914 according to both Adnyamathanha and western tradition. She was a single woman aged 38 and he was a widower of 52. Adnyamathanha country includes the glorious Flinders Ranges, but they met when both worked at a sheep station on the Western Darling River.

Born in Bow, England, Rebecca emigrated to Australia before WWI. She became known as Mrs. Widgety. After Jack died, she lived at Beltana Station but was asked to leave by the chief protector of Aborigines in Adelaide. She declined as she had children to educate and living was expensive, especially if she had to pay rent. She adopted Adnyamathanha cultural approaches. For example, she kept no photograph of Jack. ‘We never keep belongings of the dead, and always shift camp, away from the haunt of their spirit[xxxi]’. She was recommended by the South Australian Aborigines Protection Board as ‘an English woman … a person of good character’, in supporting her adult childrens’ applications for rations[xxxii].

Sunday Guardian Sun, December 18, 1932, National Library of Australia.

Minni Maynard, née Critchley

Minnie Critchley was ostracized from her working-class mining family when she married Fred Maynard in 1928. Maynard was at that time a high profile Aboriginal activist, leader of the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association and an outspoken opponent of the State government Aborigines Protection Board and its policies. It is thought that the need for the family to protect itself from continual police harassment was the cause of the families’ move into virtual hiding from society and his subsequent withdrawal from political activity[xxxiii].

Ivy Sutton

Ivy Sutton, was a blonde-haired blue-eyed girl in the 1940s. Her paternal heritage was German. Raised in Coonabarabran, New South Wales, she was thrown out of home at fourteen and sent to help her maternal aunt with a tiny baby. On returning home, she found her mother gone to live with another man and the house locked. She presented to a convent to become a nun, but was instead removed to a welfare home. Upon release, she was again destitute and still her mother did not want her.

Keith Grant, Wiradjuri man, would whistle at her as she walked by. So, Ivy moved in with him and stayed for decades raising a large brood of their children. The law took a dim view of this love. It was almost unthinkable to lawmakers that ‘a white woman would deign to love a black man’[xxxiv]. As recorded by her grandson, the Walkley Award winning journalist and television presenter, Stan Grant:

‘ worlds shook. Australia could not understand this love, so it was banned. It was a love bigger than my grandparents too, and they could never hold on to it. But Ivy stayed for thirty years and had thirteen children.

She had a hard time. She was turned away from hospital while giving birth to her first child because it was going to be the wrong colour. Police would stop her in the street and turn over her pram, searching for grog … She lived in a tin humpy with her kids, until the police came at gunpoint with a bulldozer and ran it to the ground. Two of her children died young. Ivy lived on the margins, always on the outside of town, always an outsider. Ivy was on the wrong side of the colour line in an Australia where those things matters, even though Ivy was white. In 1940s Australia, blackness was contagious.[xxxv]’

Ivy and Keith never married. Legal formalities had no real place in their lives. There was crippling poverty and severe rejection, along with constant heavy-handed police intrusion, prying welfare officers and threatened removal of her children. They lived in a dirt-floored humpy, ate skinned rabbits, played card games that lasted for days and managed hungry children. Her grandson remembers that Ivy bathed him, fed him and, each birthday, sent him knotted handkerchiefs stuffed with loose change. He describes her:

‘Icy: bright red lipstick, steel wool yellow hair and always talking. She was like a machine gun. One sentence would run into another. Often she was barely coherent, just thoughts tumbling over and over each other. She thought she was Patsy Cline. She needed no prompting to burst into song.’[xxxvi]

Eventually, the sheer hardships of life broke Ivy who fled one day and married another man within weeks, realizing too late that she could not turn back. Stan Grant believes that she never stopped loving Keith and he loved her till his dying day, noting that sometimes she would still run off with Keith and they would relive that great forbidden love.

Stan Grant dedicated his second book to Ivy – and to his wife eminent sports journalist and television presenter, Tracey Holmes:

‘white women who have loved me’[xxxvii].

1950s and 1960s

From the 1970s

White women during the 1950s and 1960s married a number of prominent Aboriginal men, e.g. footballer and Aboriginal activist Charlie Perkins, singer Harold Blair and boxer Lionel Rose. Although many were actively involved with their husbands’ prominent activities, little was known of them at that time or since and their lives appear to submerge into the Aboriginal story[xxxviii].

Since the 1970s interrelationships between white women and Aboriginal men increased and became far less fraught. Between 1991 and 1996, they accounted for 16% of Indigenous population growth. However, even then male commentators sometimes attribute this to an Aboriginal desire to ‘join mainstream society’ and ‘escape into civilisation’[xxxix]. Such a perspective entirely leaves out that these womens’ love almost certainly stood alongside fascination with Indigenous culture, kindness, spirituality, humour, connection to country and a sense of community to which their relationship with an Aboriginal man gave them access.

Heather Bonner née Ryan

Heather was the wife of Neville Bonner the first Indigenous member of the Federal Parliament and a Senator for 12 years from 1971-1983. They married in 1972, not long after he entered Parliament.

A WWII American war bride, Heather returned to Australia in the 1950s after the death of her first husband. She became active in the One People of Australia League where she met Bonner. The Queensland Times described her as “one of Ipswich’s great matriarchs and political activists”[xl] and, at her death aged 81, in October 2004, the then Queensland Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Policy issued a statement recording that, in addition to her strong support to Bonner, she ‘was also a tireless worker in her own right’. Her obituary records her daughter as saying:

“She was an incredible woman and my stepdad became her career.”[xli].

Pat Lowe[xlii]

Pat Lowe married the great Australian Indigenous artist, Jimmy Pike. Born and raised in England, she migrated to Australia in 1972 as a psychologist first in a childrens’ home and later in Western Australian prisons. It was when she transferred to Broome that she met Jimmy Pike in 1979. He was a traditional man serving a life sentence for a tribal murder. After he was granted parole, Pat and Jimmy set up camp on his Country in the Great Sandy Desert where they lived for three years before moving back to Broome. Jimmy died in 2002 but Pat remained in the same modest home they shared in Broome.

Pat had an independent and successful career as a writer, winning the Western Australian Premier’s Childrens’ Book Award in 1998. She and Jimmy worked together on a number of childrens’ books. These included Yinti: desert child, 1992, Desert Cowboy 2000, and Jimmy and Pat Meet the Queen 1997, a fantasy about Aboriginal and Crown rights over land, in which Jimmy, a traditional owner of land in the Great Sandy Desert, challenges the Queen to visit his camp and prove how she is the rightful owner of his Country. Her Majesty accepts the invitation.

Sally Dingo née Butler[xliii]

Sally married high-profile TV personality, Ernie Dingo, in 1989. She was born in 1953 in LaTrobe Tasmania, attended Penguin Primary School and Ulverstone and Burnie High Schools, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree from University of Tasmania in 1976. She worked in journalism and media sales, before becoming a lecturer in art history at University of Queensland. She is author of two books about her husband and family. She raised their daughter as well as Ernie’s daughter from a previous relationship, an adopted daughter and a grandchild.

Tracy Holmes[xliv]

Tracy Holmes, in somewhat controversial circumstances that led to her ‘sacking’, began an affair with Stan Grant (Ivy Sutton’s grandson) at the time of the Sydney Olympics in 2000 and subsequently they married. She has a highly successful media career – the first female host of a national sports program, sports presenter on Channel 7 and, currently presenter on ABC NewsRadio.

Voice, Treaty, Truth – Working Together for Shared Future

In the face of often extreme hatred, racism and prejudice,

these and many other couples were prepared to chance life together to

demonstrate the truth of their love. Until recent decades, their courage and determination

to work together in the face of opposition, demonstrated the real day-to-day

practicality of ‘working together for shared future’. Those that had children, created a living

shared future, a future that continues today and will continue into the

future.

[i] The research uncovering academic studies of historical marriages was undertaken by Cameron Algie at Kellehers. Studies of sexual interrelationships between Aboriginal men and white women is obscure and largely missing from the Australian historical landscape. Kellehers is grateful to Cameron for his careful and valuable research. This story draws extensively on the excellent paper by Victoria Haskins and John Maynard below.

[ii] Op. cit., p 191.

[iii] Haskins, Victoria and John Maynard, 2005, Sex, Race and Power: Aboriginal Men and White Women in Australian History, Australian Historical Studies, 191-216,p 191.

[iv] Haskins and Maynard, op. cit., p 203, Jenkins, G., 1985, Conquest of the Ngarrindjeri – The Story of the Lower Murray Lakes Tribes, Raukkan, Adelaide, p 230.

[v] Collins, Lieutenant David, 1791, quoted in Ann McGrath, Aboriginal-Colonial Gender Relations at Port Jackson, Australian Historical Studies, 24, no. 25 (October 1990), p 195.

[vi] McGrath, op.cit. p 202.

[vii] Quoted in H.W.H. Huntington, 1897, History of Newcastle and the Northern District, no. 14, Newcastle Morning Herald, 21 September.

[viii] This undated narrative is quote in G. Blomfield, 1988, Baal Belbora The End of the Dreaming: The Massacre of a Peaceful People, Alternative Publishing Co-operative, Sydney, p 42. Barbara Boynton’s stories also eloquently tell the reality of lives for early colonial white women e.g. Bush Studies, 1902, Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd, London, Republished 2012, Text Publishing Melbourne.

[ix] Darian-Smith, K., 1996, Rescuing Barbara Thompson and Other White Women: Captivity Narratives on Australian frontiers, in Darian-Smith, K., L. Gunner and S. Nuttall, Text, Theory, Space: Land, Literature and History in South Africa and Australia, Routledge, London.

[x] Huntington, p. cit., Haskins and Maynard, op. cit., p198.

[xi] Multiple sources are quoted by Haskins and Maynard, op. cit., p198 at footnote 27, with particularly Carr’s descriptions of the Gippsland frontier, e.g. J. Carr, 2000, The White Woman of Gippsland, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne and J. Carr, 2001, Cabin’d, Cribb’d and Confin’d: the White Woman of Gipps Land and Bungalene, in Creed, Barbara and Jeanette Hoorn, Body Trade: Captivity, Cannibalism and Colonialisation in the Pacific, Pluto Press, Sydney.

[xii] Behrendt, Larissa, 2016, Finding Eliza: Power and Colonial Storytelling, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland. Also, https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/larissa-behrendt-unpicking-the-story-of-eliza-fraser-20160126-gmdxpk.html, accessed 100719.

[xiii] Fraser, Eliza, 1837, Narrative of the capture, sufferings, and miraculous escape of Mrs. Eliza Fraser, wife of the late Captain Samuel Fraser, commander of the ship Sterling Castle, which was wrecked on 25th May, Charles S. Webb, New York. https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/21718995? Accessed 100719.

[xiv] Schaffer, Kay, 1989, Australian Mythologies: The Eliza Fraser Story and Constructions of the Feminine in Patrick White’s A Fringe of Leaves and Sidney Nolan’s ‘Eliza Fraser’ Paintings, Kunappie, Vol 11, Issue 2, University of Wollongong Australia. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f67a/c341b9afc8e07007c6575ec426b4d39eb46e.pdf accessed 100719.

[xv] White, Patrick, 1976, A Fringe of Leaves, Jonathan Cape, London.

[xvi] Ondaatje, Michael, 1971, The Man with Seven Toes, The Coach House Press, Toronto.

[xvii] Haskins and Maynard, op. cit., p 198 at footnote 28 list many primary sources recording these events – lettergram, government memo, newspaper article.

[xviii] Monticone, J., 1990, Healing the Land, Healing the Land, Canberra, p 80-81, Rimas, Peter, Wiradjuri Places: The Murrumbidgee River Basin, Volume 3, 1995, Black Mountain Projects. http://www.sydneyalternativemedia.com/blog/index.blog?entry_id=1986738 accessed 100719, https://books.google.com.au/books/about/Wiradjuri_Places.html?id=nQcFHgAACAAJ&redir_esc=y accessed 100719.

[xix] Her story is well documented due to the meticulous record made by Oswald Brierly of his contemporaneous conversations with her and his daily journal. The story was fictionalized by Ion L Idriess, 1947, Isles of Despair. See also, https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/9602097?selectedversion=NBD23018250 accessed 100719, Raymond J. Warren, 1978, Wildflower: The Barbara Crawford Thompson Story, 2nd revisions, Raymond J. Warren, https://www.pressreader.com/ accessed 100719.

[xx] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbara_Thompson_(castaway), accessed 100719.

[xxi] Moore, Islanders and Aborigines at Cape York, at p 80.

[xxii] Dondy to Protector of Aborigines, 29 March 1889, South Australian State Archives, GRG 52/1/1889/99.

[xxiii] Hunt, W. R., to Public Solicitor, 13 January 1927, South Australian State Archives, GRG 52/1/1926/37, Bourke to Chief Protector of Aborigines, 9 September 1926, South Australian State Archives, GRG 52/1/1926/48.

[xxiv] Chief Protector of Aboriginals to Secretary Public Works, 3 July 192, State Archives of South Australia, Department of Aboriginal Affairs Correspondence Files, GRG 52/1/1912/22, also Conversation with Mrs. Haskins’ daughter, in her 90s in 2005, with Victoria Haskins, Adelaide, 19 February 2002, Haskins and Maynard op. cit. footnote 51, p 203. See also, G. Jenkins, 1985, Conquest of the Ngarrindjeri – The Story of the Lower Murray Lakes Tribes, Raukkan, Adelaide, p 258.

[xxv] Moore, Laurie and Stephan Williams, 2001, The True Story of Jimmy Governor, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, p 18-19.

[xxvi] 1978, Fontana, Adelaide.

[xxvii] 1978, Angus & Robertson, London, 23-24.

[xxviii] Behrendt, Larissa, 2000, Consent in a (Neo) Colonial Society: Aboriginal Women as Sexual and Legal Other, Australian Feminist Studies, 15, no. 33, December, p 353-67.

[xxix] Ellinghaus, Katherine, 2002, Taking Assimilation to Heart: Marriages of White Women and Indigenous Men in Australia and North America, 1870s-1930s, PhD thesis, Melbourne University, p 263.

[xxx] Halse, Christine, 2002, A Terribly wild Man, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, p 83.

[xxxi] Quoted in Ellinghaus, Katherine, 2006, Taking Assimilation to Heart: Marriages of White Women and Indigenous Men in the United States and Australia, 1887-1937, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, p 152.

[xxxii] Secretary Aborigines Protection Board to Deputy Director of Rationing, 14 October [1942], State Archives of South Australia, GRG 52/1/45/1942.

[xxxiii] Maynard, John, 2003, Fred Maynard and the Awakening of Aboriginal Political Consciousness and Activism in Twentieth Century Australia, PhD thesis, University of Newcastle, p 321-2.

[xxxiv] Grant, Stan, 2016, Talking to My Country, Harper Collins, Sydney, p 91.

[xxxv] Grant, Stan, 2019, On Identity, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, p 20 – 21.

[xxxvi] Grant 2016 op. cit, p 95.

[xxxvii] Grant, Stan, 2016, Talking to My Country, Harper Collins, Sydney, frontispiece.

[xxxviii] Haskins and Maynard, op. cit. p 204-5, 213-4.

[xxxix] For example, Howson, Peter, 2004, Pointing the Bone: Reflections on the Passing of ATSIC, Quadrant, no. 407, June, p 9, 12.

[xl] https://www.moadoph.gov.au/blog/from-the-oral-history-collection-heather-bonner/ accessed 100719.

[xli] http://oa.anu.edu.au/obituary/bonner-heather-28099 accessed 090719.

[xlii] https://www.abc.net.au/radio/programs/conversations/conversations-pat-lowe/10145104, accessed 090719.

[xliii] https://www.austlit.edu.au/austlit/page/A55683 accessed 090719.

[xliv] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tracey_Holmes accessed 090719.

Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation

This fact sheet is intended only to provide a summary and general overview on matters of interest. It does not constitute legal advice. You should always seek legal and other professional advice which takes account of your individual circumstances.

Leave a Reply