Valuing Traditional Landscape

NAIDOC WEEK 2021

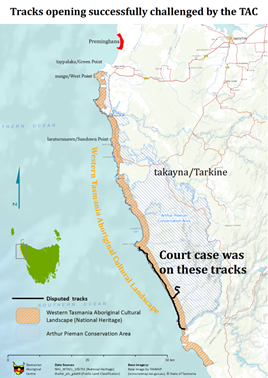

The People whose voice we recall today are the Tarkine, the traditional owners of the Sandy Cape region on the Tasmanian west coast. Their representative gave voice to protect Country known as the ‘Western Tasmania Aboriginal Cultural Landscape’ (WTACL), an impressive area of coastal strip of around 21, 000 ha that runs along the northern part of the west coast of Tasmania.[1]

Image: Map of Western Tasmania Aboriginal Cultural Landscape, 2013[2]

The Tarkine and proximate Peoples, the Pee.rapper and Mangin, inhabited the area for at least 4,000 years.

During summer, semi-sedentary ‘villages’ were established on Country. Huts, hut depressions and middens remain. Middens were living and socialising areas – houses without walls. The middens vary in size. Huts were made of pliable tree stems and, less commonly, whale rib bones. The walls were bark, grass or turf. Early white records make numerous references to Aboriginal huts including their location, construction, size and use along the entire west coast of Tasmania[3].

In winter, the village groups split into smaller groups that moved up and down the north-west coast. The hinterland was thick with tea tree scrub in a complex of swamps – and used for hunting, gathering plant foods, quarrying stone tools and trading ochre.

The Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia, in 2016[4], recorded that the Western Tasmania Aboriginal Cultural Landscape has always held a special significance for Tasmanian Aboriginal people. Ever since their removal from Country, the Aboriginal community maintained a strong interest in and connection to it, actively petitioning the British and Tasmanian Governments in pursuit of the return of land and recognition of land rights. In 1977, a petition was presented to Queen Elizabeth II, during her Royal visit, for the recognition of prior Aboriginal ownership, return of all sacred sites, mutton bird islands and Crown land, in addition to compensation. Aboriginal People continue to play a key role in the management of this Country to ensure its preservation for future generations. An achingly sad biography of Truganini[5] described the early wanderings of George Augustus Robinson, protector of Aborigines, amid the vagaries of the mischievous People, through their Country.

The Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre[6] is an Aboriginal community organisation developed in the early 1970s. It represents the political and community development aspirations of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community.

In the face of plans to designate tracks through the Western Tasmanian Aboriginal Cultural Landscape to open it up for recreational vehicles, the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre presented to the Court. The proposal, developed by two Tasmanian government bodies, involved constructing new track sections, spreading gravel, laying rubber matting, installing culverts, fencing and track markets. These works were likely to have a significant impact on the cultural heritage value of the place.

The Western Tasmania Aboriginal Cultural Landscape is included on the National Heritage List. Its gazetted Value is:

‘During the late Holocene Aboriginal people on the west coast of Tasmania and the southwestern coast of Victoria developed a specialised and more sedentary way of life based on a strikingly low level of coastal fishing and dependence on seals, shellfish and land mammals …

This way of life is represented by Aboriginal shell middens which lack the remains of bony fish, but contain ‘hut depressions’ which sometimes form semi-sedentary villages. Nearby some of these villages are circular pits in cobble beaches which the Aboriginal community believes are seal hunting hides …

The Western Tasmania Aboriginal Cultural Landscape has the greatest number, diversity and density of Aboriginal hut depressions in Australia. The hut depressions together with seal hunting hides and middens lacking fish bones on the Tarkine coast … are remarkable expressions of the specialised and more sedentary Aboriginal way of life.’

Its inclusion on the National Heritage List brought the site within the provisions of the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). The question was whether a proposed designation by the government bodies and the attaching of conditions to that designation was a ‘controlled action’ under EPBC Act. A ‘controlled action’ required the Federal Minister’s approval. Having determined that there was a ‘controlled action’, the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia needed to decide how the law should identify the relevant national heritage values, in this case the Indigenous heritage value.

The primary judge had held that the gazetted description of the National heritage values, was not itself the value. She found that the ‘value’ is the broader statutory concept of Indigenous heritage values, which she found was identified by evidence and proof at trial. The Full Court disagreed that evidence was relevant. It found that:

‘National Heritage values … are the values included in the National Heritage List’.

This warns Indigenous Peoples as to the very great care they must take to ensure that the Value statement in any National Heritage listing of Country fully and accurately reflects their values.

The Full Court agreed that the Listed Value may be capable of explanation or contextualisation by other material – that the Values ‘are not a statute’[7] but an expression of a value both sophisticated and complex that may need to be understood or explained…’. The context and background, it held, may include other material in, or referred to in, the National Heritage List, being the history of the area and the full cultural and historical significance of what can still be found there.’ It referred to the ‘history and significance described in the Australian Heritage Database’, which it found ‘provides a resource which assists in understanding the statement of value. To appreciate this context and the cultural history of the area is not to depart from the value in List; it is to explain it, or at least to understand it.’[8]

The court rejected the use of expert and lay evidence as to value. Nevertheless, it found that it was it ‘perhaps unwise to be dogmatic about what kind of evidence would be permissible to explain or understand a statement of value in the National Heritage List; for instance, there would seem little offence in an expert explaining what a “hut depression” or “midden” was if the referenced material in the National Heritage List did not do so.[9]’

…

Tiphanie Acreman was junior counsel in this case.

Having completed undergraduate degrees in Law and Science from the University of Tasmania, Tiphanie moved to Melbourne, initially working as a judge’s associate and then commencing practice at the Victorian Bar. In 2014, she was approached by the Environmental Defender’s Office Tasmania (EDO) on behalf of its client the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre (TAC). The TAC held concerns over the government proposal within takayna / the Tarkine on the west coast of Tasmania, as the WTACL is a listed National Heritage Place containing evidence of the continuous occupation and spiritual connection of Tasmanian Aboriginal peoples including hut depressions, high density midden deposits, petroglyphs and known burial sites.

“The case was the first judicial decision considering the protection of “National heritage values” in the context of “Indigenous heritage values”. I knew there wasn’t any case law on this aspect of the EPBC Act so I realised early on that the case had the potential to establish precedent for other areas of indigenous heritage under the commonwealth legislation.”

At trial, the government argued that, provided the plans to build did not go over the hut depressions and infringe on the pinpointed heritage areas, it was justified to have a road running through the landscape.

However, like Mr Steve Compton of Bunurong Country who spoke of Toomuc Creek,[11] Aboriginal People “were arguing that it was the landscape that is the heritage, so it is not just individual pinpoints that you need to avoid.”

“It’s about whether or not you should have drivers and roads going through the landscape at all.”

The TAC won at trial and the case was appealed by the Tasmanian government. During the appeal, the Tasmanian government agreed to refer the proposal to the Commonwealth for assessment under the EPBC Act. Ultimately, the Commonwealth determined that the proposal was likely to have a significant impact upon a matter of National Environmental Significance and would require a full assessment.

The proposal was not progressed further and the area remains closed to four-wheel driving to this day, “So the community, both indigenous and non-indigenous, can experience the vast area of the WTACL in its entirety without post-colonial built form. It really is a breathtaking place.”

The case highlights a common misconception regarding cultural heritage, that is that heritage is a particular “thing” in the landscape, such as a hut depression or a petroglyph. But connection to Country and protection of the cultural aspect of a landscape requires more than a piece-meal approach.

As Ms Acreman puts it:

“Cultural heritage isn’t just a dot on a map. It’s an experience when you are there. It’s the dots put together and experienced in their context. That is what needs to be protected.”

KELLEHERS AUSTRALIA

7 July 2021

Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation

This fact sheet is intended only to provide a summary and general overview on matters of interest. It does not constitute legal advice. You should always seek legal and other professional advice which takes account of your individual circumstances.

[1] Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre Incorporated v Secretary, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (No 2) [2016] FCA 168 [1].

[2] Environment Research and Information Branch, Australian Government Department of sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (web) [accessed 7 July 2021] https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/d3456005-87a2-4c69-beb9-3223499797bf/files/boundary-map.pdf.

[3] ‘National Heritage Places – Western Tasmania Aboriginal Cultural Landscape’, Australian Government: Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (web) [accessed 7 July 2021] < https://www.environment.gov.au/heritage/places/national/western-tasmania>.

[4] Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre Incorporated v Secretary, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (No 2) [2016] FCA 168

[5] Phybus, Cassandra, 2020, Truganini: Journey Through the Apocalyse, Allen & Unwin New South Wales.

[6] Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre (web) [accessed 7 July 2021] < https://tacinc.com.au/>.

[7] Secretary, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment v Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre Incorporated [2016] FCAFC 129, 86, 87.

[8] Ibid 88.

[9] Secretary, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment v Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre Incorporated [2016] FCAFC 129, 89.

[10] The Wilderness Society.

[11] ‘The Vibrant Life of Indigenous Relics’, Kellehers Australia, NAIDOC Week (web) <https://kellehers.com.au/latest-news/the-vibrant-life-of-indigenous-relics/>

Leave a Reply