‘It’s harrowing to go back over the research but it was so empowering. You’ve gotta know this knowledge’[1].

World’s Most Liveable City

Melbourne is repeatedly awarded the World’s Most Livable City[2].

Frankly, this prosperity comes at the price of Aboriginal blood and suffering. We have indeed ‘gotta know this knowledge’ – awful as it is.

The truth of Narrm’s (Melbourne’s) history lies hidden in plain sight.

This is our sad ending to NAIDOC 2020 after the power of Waa and rich Indigenous storytelling. It must be recognized and it must be told. It must be taught and redressed – and not with tokenism.

Early Days

Wurundjeri knew of the sealers, French ships and overland explorers[4]. Although not saltwater People, they knew whalers and of the whitefellas arriving in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land. Communication between Aboriginal Peoples across Australia is generally good and most have great language skills. Some say early occupiers of far western New South Wales found local Aboriginal People fluent in Gaelic that they learnt from escaped convicts.

William Buckley received welcome by the Peoples of Port Phillip Bay after escaping from the British penal outpost briefly created on Bunarong Country at Sorrento in 1803. Charles Grimes, Surveyor-General of New South Wales, rowed up the Yarra to Dights Falls in February 1803. The Wurundjeri were highly intelligent and sophisticated people, connected across the continent and skilled negotiators. They knew the danger and Buckley forewarned them.

Some feared the sky would fall in. There was a spirit pillar holding it up, but they needed:

‘to repair a new prop for the sky, as the present [one] had become rotten and … destruction was inevitable should the sky fall upon them’[5].

They needed ‘to prevent so dreadful a catastrophe’[6].

After John Batman made his treaty with the Wurundjeri on 8 June 1835, a group of men, with their animals, gradually took up occupation of an agreed area. William Barak, in his short memoir My Words[7], recollected Batman’s arrival:

‘I never forget it … (A)ll the blacks camped at Muddy Creek. Next morning they all went to see Bateman, old man and woman and children, and they all went to Bateman’s house for rations, everything ready there, and killed some sheep by Bateman’s order. Buckley told the blacks to look at Bateman’s face, he looks very white, any man that you see out in the bush not to touch the bread in it. Make a camp outside and wait till the man comes home, and find everything safe in the house. They are good people. If you kill one white man, white fellows will shoot you down like a kangaroo.’[8](sic).

We recommend you read the ‘contextual understanding’ of Barak’s important story My Words via this link:

http://reconciliation-manningham.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Barak-My-Story.pdf[9]

For the next year, the camp at Narrm comprised a small group of strangers that the Wurundjeri permitted onto their Country.

‘(They) did not chance upon an unknown place. The advantages of the Melbourne region had been known for millennia. John Batman and the other would-be founders of Melbourne merely recognized what had long been obvious: this was a place where homo sapiens might thrive.’[10]

Immediately upon learning of Batman’s treaty, Governor Burke, thundered from Sydney, forcefully rejecting it by Proclamation on 26 August 1835.

Over the next year, submissions went back and fro to London from Sydney and Van Diemen’s Land. Some supported negotiated arrangement with the Wurundjeri Elders. Others asserted Crown sovereignty and urged England to immediately open up this bountiful area for agriculture. We found no record of consultation with the Wurundjeri by London, Sydney or Van Diemen’s Land.

On 1 September 1836, Bourke received the British government’s authorization for ‘legal settlement of the district’ and its rejection of the negotiated agreement. Within weeks, the British government was at Port Phillip[12].

…

What happened then is hard to write – and it is almost inconceivable that forebears of contemporary non-Indigenous Melbournians gave effect to this; or watched it happen without action or apparent protest[13].

Surveyor Wedge, who by then was a member of Batman’s group complained that:

‘… (T)he natives still expect to receive from our hands the fulfilment of the treaty – nor can they be made to understand the true bearing of Sir Richard Bourke’s arrangement… the onus of keeping up the friendly intercourse that was established by the treaty of 1835 [still] devolves on us’[14]

Let us set the scene, in a description of the Wurundjeri ceremony, Tanderrum (welcoming strangers) that had so often greeted William Buckley and John Batman’s group:

‘There is not, perhaps, a more pleasing sight in a native encampment than when strange blacks arrive who have never been in the country before. Each comes with fire in hand (always bark) which is supposed to purify the air … They are ushered in generally by some of the intermediate tribe, who are friends of both parties … the aged are brought forward and introduced. The ceremony of Tanderrum is commenced: the tribe visited may be seen lopping boughs from one tree and another, as varied as possible of each tree with leaves; each family has a separate seat, raised about 8 or 10 inches[15] from the ground … Two fires are made, one for the males and the other for the females. The visitors are attended on the first day by those whose country they are come to visit, and are not allowed to do anything for themselves; water is brought to them which is carefully stirred by the attendant with a reed, and then given them to drink (males attend males and females female); victuals are then brought and laid before them, constituting of as great a variety as the bush in the new country affords … during this ceremony the greatest silence prevails … You may sometimes perceive an aged man seated, the tear of gratitude stealing down his murky, wrinkled face. At night their mia-mias (huts) are made for them; conversation, &c. ensue. The meaning of this is a hearty welcome. As the boughs on which they sit are from various trees, so they are welcome to every tree in the forest. The water stirred with a reed means that no weapon shall ever be raised against them.’ [16], [17]

…

The British Arrive

From the arrival of the British government, with its troops and officials, a land rush and squatter invasion exploded. On a 10 pound licence to use ‘Crown’ land, squatters took possession with impunity. Wurundjeri ‘found upon their own property’ that they were ‘treated as thieves and robbers’ and ‘driven back into the interior as if they were dogs or kangaroos’[18]. ‘During this frenetic invasion, the frontier extended at a rate of around one hundred miles a year to the west and north. Aborigines were largely dispossessed of a territory bigger than England in just five years.’[19] Massacres invariably preceded squatters. Henchmen able to ‘secure’ a squatting run set about eradicating the Aboriginal People of the land. Squatter Neil Black, wrote in 1839 that one must ‘slaughter natives right and left’ to take up a run, that ‘many people bounce [brag] about their treatment of the natives’ and ‘that two thirds of them does not care a single straw about taking the life of a native provided they are not taken up by the Protector’[20].

Whilst squatters began taking Wurundjeri land, what happened in Narrm (Melbourne) was more subtle – but with dreaded consequences. Townships:

‘involved greater numbers of Europeans, more substantial structures and offered local clans less hope for respite from the disruptions of European lifeways. … The establishment of settlements led to the development of agencies of control and the introduction of policing. Settlements were equipped with the means to safeguard property and people. … Townships also contained many features that were attractive to Aboriginal people. Although township heralded permanent change and disruption, they nevertheless possessed a magnetism that proved fatal in many instances. They were exotic places where unusual people lived with strange possessions and animals.’’[21].

Van Diemen’s Land Lieutenant Governor George Arthur was frank:

‘it is better for all parties to be sincere and plainly state that the occupation of a good run for sheep has been the primary consideration, if not the only one’[22].

Of course, the Wurundjeri and other Peoples forcibly resisted:

‘certain tribes on the road to and in the neighbourhood of Port Phillip have lately assumed a hostile attitude towards the settlers and have committed many murders and other outrages upon them … (T)they are assembled in large numbers armed and attacking such persons as are most unprotected and within their reach so that many have been obliged to abandon their stations…’[23]

Conflict occurred with traditional culture. A ceremony called mur.re.ne.rere was to occur. Restrictions applied that Europeans should not witness. It involved Woi wurrung, Boonwurrung and Daungwurrung.[24] Aboriginal people found ways around the new laws regulating their access to land.

‘The introduction of a law prohibiting unregistered dogs from entering Melbourne provoked a ‘strong and bitter reaction’ from Aboriginal people. In response, women took charge of the dogs and remained on the outskirts of the settlement, while the men went to town to procure their wants: food, money, tobacco and liquor’[25].

By early 1839, Aborigines were:

‘almost in a state of starvation and (could) only obtain food day by day, by begging’. … (Hunting was) ‘abandoned on account of their game being driven away by the encroachment of settlers, and the roots on which they used partially to feed have been destroyed by the sheep’[26].

Wurundjeri women sold bulen-bulen (lyre bird) feathers to namadjidj (white man)[27]. The djilendja (policeman) entered Wurundjeri lives. The town itself was unhealthy with waterways polluted, household and slaughterhouse refuse deposited promiscuously in the streets and diseases of infantile cholera and dysentery rife, as well as typhoid[28].

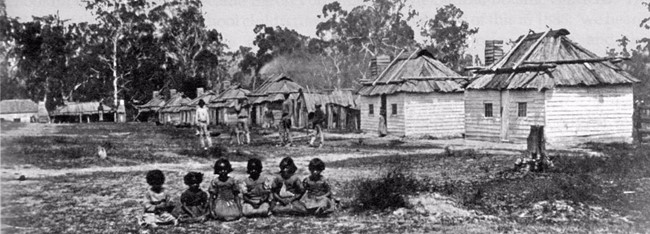

In her recent biography of Truganini, distinguished historian Cassandra Pybus describes Truganini’s arrival from Van Diemen’s Land in February 1839.:

‘Beyond the tents of the assistant protectors there was little to see except a forlorn collection of twig and bark shelters …, where dozens of the local Kulin people huddled around, barely covered by ragged blankets. They were obviously unwell. Across the river, only a ruined landscape of huge blackened tree stumps and one small wooded hill could be seen; the town of Melbourne was out of sight. At the base of this hill was a log house and vegetable garden, home of their old foe John Batman.’[29]

Funding cuts occurred to the Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate from 1843-1850. This reduced staff numbers and medical support, with the Protectorate’s work extending over a greater territory with fewer staff[30].

Hunger was a continual issue:

‘the bush big one hungry no belly full like it Melbourne’[31].

Wurundjeri children, women and men, literally died of hunger – here, on this very spot – the world’s most liveable city.

Let us pause and pay our respects to each and every one of these people.

…

Later Days

In 1862, land was gazetted for the Wurundjeri at Coranderrk in Healesville, 60km east of Melbourne. Simon Wonga (Billibellary’s son) and William Barak led their People to their new land. The farm prospered with a thriving village including a school, dairy, church, bakery, hop kilns and orphans’ dormitories. Pastor John Green was ‘manager’. The government soon doubled the size of the Reserve.

By the 1860s, wirengel[33] (native dog) was in trouble:

‘the “dingo, or native dog, so destructive of our flocks, but which the increasing warfare waged by the squatter is gradually exterminating’. (sic)[34]

Anthony Trollope visited Melbourne in the early 1870s, writing that the city had largely turned its back to Birrarung, drained the swamps, filled in the lakes and flattened the hills[35].

In the 1870s, pressure came to subdivide the Corranderrk Reserve land and again shift the Wurundjeri, this time entirely off Country to a remote location on the Murray River. Barak responded:

‘Me no leave it, Yarra, my country. There’s no mountains for me on the Murray.’

Barak launched a second walk of his People – this time to Parliament House. The Wurundjeri saved the Reserve, although funding was cut. The people at Coranderrk began to drift into poverty.

Again, in 1881, Barak had to organize a third long walk of his People which resulted in the then Chief Secretary, Graham Berry, appointing a Board of Inquiry. Its report resulted in the Reserve continuing.

However, finally in 1924, the Coranderrk Reserve was closed and residents were encouraged to now finally move off Wurundjeri Country to Lake Tyers Mission in Gippsland – although nine refused to go.

…

When next walking to the MCG from Birrarung (Yarra River), across the William Barak Bridge, think of Barak – a truly great man in Victoria’s history. And never forget the Wurundjeri suffering. Our State’s capital city is permeated with this grief. Australia is lessened by its silencing.

…

Let us pause again.

…

For those of us who’ve lived a COVID lockdown on Wurundjeri Country, let’s reflect. Imagine our confined time lived without food. Imagine, strangers forcibly removing us from our homes, gardens and neighbourhoods. Imagine a lockdown lived in daily fear of imminent death and danger. Imagine no Daniel Andrews reporting daily and enforcing community safety.

Let’s just sit with that.

…

Who were these British government officials? By what ‘legal’ or moral law did they bring starvation and death to this place? They offered no gentle gracious welcome from the tops of the trees to the ends of their roots. They shared no eucalypt branches, made up no comfortable nighttime huts. Imagine the sorrow. Imagine the grief.

Imagine the loneliness – and just imagine that isolation. Imagine the terror. Imagine the raging sense of injustice. A People gazing and asking ‘why?’.

…

As Boyce stridently questions:

‘How can it be that 175 years after this defining decision in Australian history was taken, it is yet to be condemned?’[36]

We are now nearly 185 years on – and still no condemnation. The world’s most liveable city hides its story in plain sight.

Government policy drove this land ‘rush’ – with no regulation slowing settlement to allow time for cultural adaptation. It failed entirely to consult with the People directly affected by the policy. As Coranderrk shows, the Wurundjeri People successfully established ‘western’ farming practices and villages. Boyce ties this land resource ‘rush’ to climate change. He sees an ingrained Australian assumption that regulation is was impossible in a ‘rush’. Also, the British quickly found regulation to secure mining revenue from the gold ‘rush’. Boyce and Guy Pearse[37] critique an ‘inability to imagine something different’[38]. The legacy of the political and policy decisions made after the founding Melbourne warn that it may not be Aboriginal People alone who suffer contemporary dangers.[39].

Wurundjeri People starved and died here. They were shot like kangaroos. The very house we live in or the gardens we walk through may be where they died. Think about this.

Melbourne is unliveable if we fail to grieve and commemorate these dead. All must tell this story. All must acknowledge the truth. All our children must be taught the story.

No-one paid the Wurundjeri for their land. They had no compensation. Their families today know this.

You are allowed to be fierce against loss, deprivation and injustice[40].

‘You wonder why sometimes you can’t reach me?

I keep going back.

I keep trying to picture my life against all this history,

Raven in the beginning

hopping about like he just couldn’t do enough.’[41].

ALWAYS WAS, ALWAYS WILL BE[42]

KELLEHERS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD

13 NOVEMBER 2020

Download a PDF of this Article HERE

Liability limited by a Scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation

[1] Purcell, Leah, Murgon’s Shining Star: Leah Purcell, ABC Radio podcast, The Conversation, Richard Fidler. Accessed 20102020.

[2] The award is bestowed by The Intelligence Unit of the Economist Group, publishers of the London based weekly newspaper The Economist, https://www.eiu.com/topic/liveability and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economist_Group, both accessed 12112020.

[3] https://global.vic.gov.au/victorias-capabilities/why-melbourne/worlds-2nd-most-liveable-city accessed 11112020.

[4] Barak confirmed their knowledge of Hume & Hovell’s explorations to WesternPort. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4407599 accessed 12112020.

[5] Related by William Buckley, HRV, 2A, 176-190, referenced in Boyce, Boyce, James, 1835:The Founding of Melbourne & The Conquest of Australia, Black Inc, Carlton, 15.

[6] Ibid.

[7] https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4407599 accessed 09112020.

[8] Ibid. See also, Wiencke, Shirley W., 1984, When the Wattles Bloom Again: The Life and Times of William Barak, self published, 3.

[9] You will notice that earlier this week, we incorrectly described Barak as the son of Bellibellary. He was the sone of Headman Bebejern. His cousin, Simon Wonga the son of ‘songman Billibelleri. Keelbundoora and Jika Jika were the sones of Jagga-Jagga (the law enforcer and Kidney-fat Man). We deeply regret any distress caused to descendants due to this error. Barak married twice – to Lizzie and Annie who gave birth to a son, David. Both Annie and David died of tuberculosis. https://cv.vic.gov.au/stories/aboriginal-culture/william-barak/william-barak-king-of-the-yarra/, accessed 12112020.

[10] Boyce, James, 1835:The Founding of Melbourne & The Conquest of Australia, Black Inc, Carlton, 8.

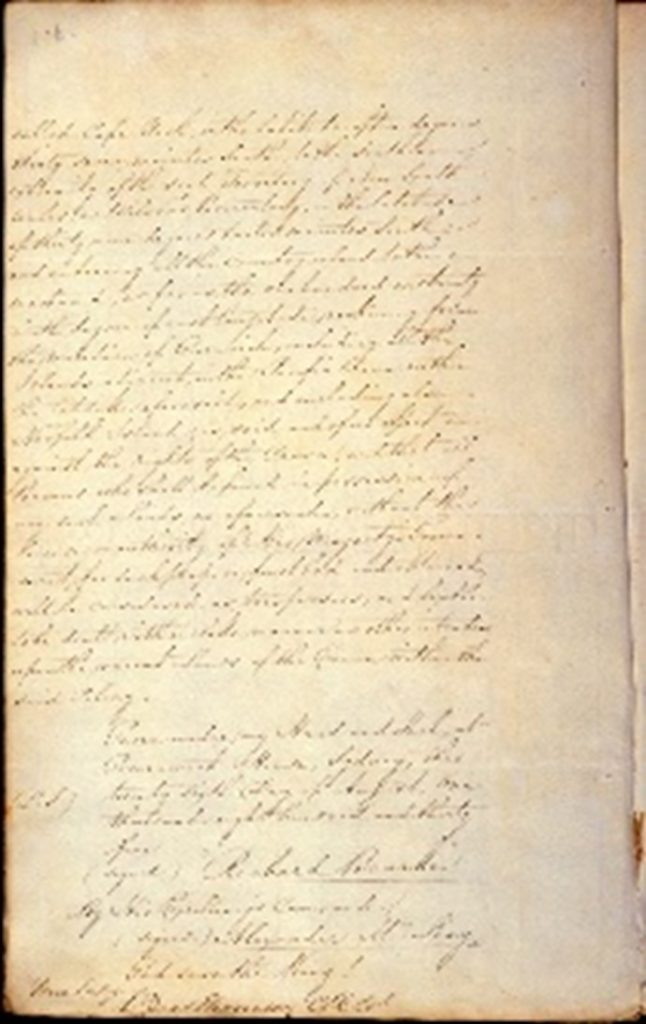

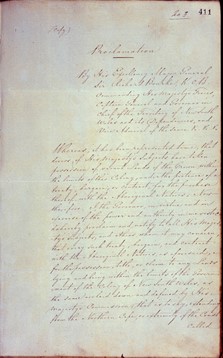

[11] Copy of Bourkes Proclamation retained by the British Colonial Office and currently held by the National Archives of the United Kingdom. The original Proclamation has not been located. https://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/scan-sid-287.html accessed 12112020.

[12] Boyce, op. cit., 142.

[13] One branch of Dr Kelleher’s family, for example, arrived in Melbourne in 1839 as poor assisted ‘bounty’ migrants.

[14] Stephen, Alfred, 1834, correspondence to Colonial Secretary Burnett, 3 November, State Library of Victoria, M5082 Box 52/2 (3), referred to in Boyce, op. cit., 71 and 218.

[15] 0.20 and 0.25 metres.

[16] Bride, Thomas, Francis (ed.), 1898, Letters from Victorian Pioneers, Trustees of the Public Library, Melbourne, 97-98, referenced in Boyce, op. cit., 36-37 and 222.

[17] https://www.mannagum.org.au/manna_matters/august-2017/news_from_manna_gum accessed 13112020.

[18] Campbell, Alistair, 1987,, John Batman and the Aborigines, Kibble Books, Malmsbury, Victoria, 171.

[19] Broome, Richard, 2005, Aboriginal Victorians: A History Since 1800, Allen & Unwin, 20.

[20] Critchett, Jan, 1990, A ‘Distant Field of Murder’:Western District Frontier 1834-1848, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 127.

[21] Clark, Ian and Toby Heydon, 2004, A Bend in the Yarra: A History of the Merri Creek Protectorate Station and Merri Creek Aboriginal School 1841-1851, Aboriginal Studies Press for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islander Studies, 13.

[22] Batman, John, 1829, correspondence to Anstley, 7 September, AOT, CSO1/320/7578, cited in Campbell op. cit. and referred to in Boyce, op. cit., 148.

[23] King, Phillip G. et al, 1838, correspondence to Gipps, 8 June, HRV 2A, 349-351.

[24] Robinson, George A., 1839, Journal, 20th November. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney holds Robinsons’ Papers, including Letterbooks, 1839-1849, MSS. A 7045-52, Correspondence and Other Papers, 1837-1865, MSS. A 7061, Correspondence and Other Papers, 1838-1849, MSS. A 7075, Miscellaneous Papers, 1839-1849, MSS. A 7079-84.

[25] Thomas, W., 1844, December 1, in VPRS 4410, Item 82, 16 volumes and eight boxes of papers, journals, letterbooks, reports, and correspondence uncatalogued MSS, set 214, items 1-24, as cited in Clark, Ian and Toby Heydon, op.cit., 41 and 82.

[26] Orton, Joseph, 1839, correspondence to Wesleyan Missionary Society, HRV 2A, 99-101.

[27] Hercus, L.A., Victorian Languages: A Late Survey, Pacific Linguistics Series B – No 77, Department of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University, 236.

[28] Grant, James and Geoffrey Serle, 1957, The Melbourne Scene: 1803-1956, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne,8.

[29] Pybus, Cassandra, 2020, Truganini: Journey through the apocalypse, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 184.

[30] Clark & Heydon, op.cit., 33.

[31] Thomas, W., 1844, Papers, VPRS 4410, Item 82, 1 December. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney holds Thomas’ Papers, 16 volumes and eight boxes of papers, journals, letterbooks, reports, and correspondence, uncatalogued MSS, set 214, items 1-24.

[32] https://www.deadlystory.com/page/culture/history/Coranderrk

[33] Hercus, op. cit., 236.

[34] 1868, Bone Cave, Mount Macedon, Illustrated Sydney News, Fri 4 September, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/63514152, accessed 06042020.

[35] Trollope, Anthony, 1873, Australia and New Zealand, Chapman and Hall, London, 281-2.

[36] Boyce, op. cit, 33.

[37] Boyce, op. cit.

[38] Pearse, Guy, 2009, Quarry Vision: Coal, Climate Change and the End of the Resources Boom, Quarterly Essay, Black Inc, Melbourne, 33.

[39] Boyce, op. cit, 206-7.

[40] Adapted from the poem Worldwork. Marburg, Marlene, 2016, Worldwork, Grace Undone: Encounter, Windsor Scroll Publishing, 137.

[41] Davis, H., Robert, 2009, from Saginaw Bay: I Keep Going Back, Alaskan Quarterly Review, Vol. 26, No. 1 and 2. Spring/Summer, https://agreview.org/saginaw-bay-i-keep-going-back/, accessed 08112020.

[42] Preparation of the KA NAIDOC 2020 series has been a team effort, but we acknowledge particularly the valuable contributions of Hubert Algie, Samantha Thorogood and Rashini Perera. We drew on the magnificent library of Aboriginal books and resources built up over many years by Cameron Algie. We again thank Rebecca McFarlane, Chief Executive Officer, Melbourne Writers Festival for her enthusiastic support. Dr Kelleher also thanks her writing companions, Bronwyn Coulstock and Bernadette Miles, and Yale University writers, Amber Adams, Ky Owen and Stuart Tisdale – away writers block!

Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation

This fact sheet is intended only to provide a summary and general overview on matters of interest. It does not constitute legal advice. You should always seek legal and other professional advice which takes account of your individual circumstances.

Leave a Reply