Indigenous culture is an oral storytelling tradition. Stories and songs are sophisticated. They’ve been passed on for millennia. Gradual learning. Infinite knowledge.

All the qualities of fine literature are highly finessed – poetry, rhyme, patois, character development, hero stories of brave creation beings, spirit birds. Like finest poetry, there are layers & layers of meaning. Tales for boys only. Whispers by aunties to little girls. Air and freedom. Imagination. Dreaming.

Listen and learn. Listen. Learn.

You’ll be given knowledge as you earn it. You won’t know when it’s denied you. When you are given it, the magic and connection is vast. You’ll dream deep into it.

This is our Australian treasure.

Clear the path for Indigenous writers. Embrace and celebrate Indigenous writing, song and dance. It is the path forward for all Australians.

Past Indigenous Writers

Indigenous stories were long told to the first whitefellas and those who followed them – the protectors[1], missionaries[2], explorers[3], surveyors[4], anthropologists[5] and linguists[6]. Stories were passed on in friendship. Patyegarang[7] at just 15 years old, was guide and language teacher to Lieutenant William Dawes aboard the first fleet. In 2014, Bangarra Dance, created a major work celebrating Patyegarang[8][9].

The passing of knowledge of these stories continued into the 1950s and 1960s. Aldo Massola, a Melbourne Museum curator, recorded such stories[10]. Banjo Clarke told his story to Camilla Chance[11]. The website of the Wurundjeri[12] and Culture Victoria[13] capture multiple wonderful stories told by the Wurundjeri People.

They are all there – hidden in plain sight.

Despite the hardships dispensed to Aboriginal People by whitefellas in the development of Australia, they continue to share their stories with whitefellas, although those stories are not always ‘heard’.

ALWAYS WAS, ALWAYS WILL BE

From earliest days, Aboriginal People wrote their own stories – as they learnt the new English language.

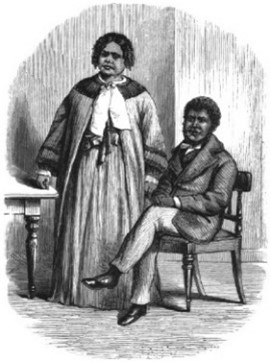

The Flinders Island Chronicle was produced by two Indigenous teenagers, Walter George Arthur and Thomas Brune, between September 1836 and December 1837. [14] After a brief education at the austere, squalid King’s Orphan School outside Hobart[15], they displayed ‘remarkable writing talent given their minimal training, and a fine copperplate hand’ [16].

Thomas Brune[17], from Nuenonne (Bruny Island) off the south-east coast of Lutruwita (Tasmania) described the women of his community:

‘… some of the woman are industrious and strong women they goes and gets the gras every morning and then goes to their schools and then go home to their own houses.’ (sic)[18].

Likely Australia’s first Indigenous journalist, he was a six year old orphan when then missionary, George Augustus Robinson (from 1838 Chief Protector of Aborigines for the Port Phillip District), arrived[19]. Returned at age 13, his unrecorded Nuenonne name had changed to Thomas Brune[20]. Brune, with a group including Truganini, travelled with Robinson to Naaarm (Melbourne) in February 1839. By April he was gone, never to return. Recorded as travelling with another Aboriginal man and two Bunurong women between the Dandenongs and Mornington Peninsula, camped at Arthur’s Seat for Christmas 1840 – like many Melbournians. By New Year he was working on Torbinurruck run on Lang Lang River near the head of Westernport. He fell from a tree whilst hunting possum and died on 3 January 1841[21].

Aboriginal writers continued writing in English. In 1964, Oodgeroo Noonuccal (Kath Walker)[22] was the first Aboriginal Australian to publish a book of verse[23][24].

In the 1970s, Jack Davis[25] drew on Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s poetry book and published his collection of poems The First Born[26]. He later wrote many plays (including children’s plays), such as Kullark[27] and No Sugar[28]. Woi wurrung lawyer and activist, Burnum Burnum[29], author of Burnum Burnum’s Aboriginal Australia: A Traveller’s Guide, was a forerunner of Marcia Langton’s recent Welcome to Country: A Travel Guide to Indigenous Australia[30]. Marcia Langton has long worked and resided on Wurundjeri land.

Reading Indigenous Writers

Astonishingly, a recent Melbourne University study found that, despite dozens of texts in the Victorian senior English curriculum lists, there is only one from an Indigenous creator[31]. Melbourne University is, of course, located on Wurundjeri land. Across a 10-year sample, the study found that less than 2% of texts from Victoria’s senior English curriculum included works by Indigenous writers – and when film was included this only increased to 4%.[32] Exceptions were Jack Davis’ No Sugar, which appeared multiple times, and Larissa Behrendt’s Home[33].

These findings record a perpetuation of silencing and denial. Assuming the findings are correct, this seems both hypocrisy and stupidity. Why ignore our Nation’s storytellers, drawn from the sophisticated oral storytelling heritage of our continent? Let’s give the Arabian Nights, One Thousand and One Nights[34], the Irish sagas and western fairy tales a break; and enrich our Australian literary souls.

‘(This) is the story we tell ourselves and our children about ourselves and our world as it was, as it is now, and as it will be’[35].

Quite apart from silencing Indigenous voice, de-colonised ways of teaching and learning help students of minority backgrounds, particularly girls, to develop a cosmopolitan sensibility[36] and recognize their unique and important place in multi-cultural Australia where they frequently experience discrimination and racism.

It is not that there are not worthy Indigenous candidates. Award winning Aboriginal authors are multiple winners of prestigious literary prizes open to all Australian writers –Miles Franklin, Premiers’ Awards, Stella, Children’s’ Book of the Year and many, many others.

For example, Indigenous authors have won the Miles Franklin Award – Kim Scott for Benang[37]in2000. He was the first Indigenous writer to win this Award. Alexis Wright won it in 2007 for Carpentaria[38]and Tarra June Winch won earlier this year for The Yield[39].

Stella Prize winners include Alexis Wright in 2018 for Tracker[40]. Children’s Book Awards have gone to Bruce Pascoe’s, Young Dark Emu[41]and Professor Aunty Joy Murphy’s two books[42]. And who could forget Rabbit Proof Fence, by Doris Pilkington[43] – both film and book.

During this year’s Melbourne Writers Festival (MWF), a remarkable session matched Indigenous poets with Indigenous astronomers, hosted by an Indigenous writer[44]. This spell-binding event explored ancient Aboriginal storytelling and, previously ignored, scientific data contained in Indigenous oral histories of the stars and cosmos. Surely, such writing alone qualifies for inclusion in Victorian curricula across multiple subject areas.[45]

The Melbourne University study did not call on us to respond to the curriculum gap by removing non-Indigenous writing that stereotypes or whitewashes Australia’s past and replaces it with a ‘golden age of Indigenous story-telling’. It recognized that settler literature reveals slices of settler consciousness about Aboriginal people [46] and provides opportunity to critique the stories they tell of Australia’s past[47].

Wurundjeri Writers

And what of contemporary Wurundjeri writers. There is a young new age of Indigenous writers – their new voice is emerging. We must embrace and support them.

Mandy Nicholson[48][49]) is a Wirundjeri willam traditional custodian of Narrm (Melbourne) and its surrounds. Her amazing work in re-capturing the subtle story and tradition of Wurundjeri women is well described orally by her, in a piece written by young Wurundjeri woman, Georgia Capocchi-Hunter:

‘Throughout my years of research, I came a across a ceremony for young Wurundjeri girls called ‘Murrum Turrukurruk’, meaning Murrum/Murrum =body; Turru/Turruk/Toorak=reeds; and kurruk/grook=suffix meaning female. It is a whole of community ceremony where young girls are put through to welcome them as women, while the young men of the community promise to protect them like brothers throughout their lives. This ceremony has been sleeping for over 180 years, we woke it up 5 years ago by putting through 20 young Wurundjeri girls and a some from other areas that don’t have access to this kind of ceremony. They were taught how to collect ochre to paint their bodies, and reeds for their necklaces. They were also presented with a possum skin belt to be worn when they dance or at ceremonies. They were taught how to be respectful, staunch young black women. If they chose to do something against what they have been taught, their belts are taken from them and they have to earn them back. It’s all about teaching them to respect themselves and culture as the same thing, if they disrespect themselves, they disrespect culture. Two of my Elders, Aunty Diane Kerr and Aunty Irene Morris also put me through the ceremony as I had no opportunity when I was a teenager.’[50] (sic).

Georgia Mae Capocchi-Hunter[51] writes for Deadly Story. Deadly Story, a wonderful website, with a particular segment for ’My Stories’. It provides:

‘A place for Aboriginal Culture, Country & Community.A place to grow my knowledge & be proud’[52].

Georgia also has a personal blog[53] and dances with Nicholson’s Djirri Djirri dance group. Read her pieces on the 2018 and 2019 NAIDOC themes – ‘Because of Her We Can’ and ‘Voice, Treaty, Truth‘.[54]

Tony Briggs[55] is the creator and writer of the hugely successful feature film The Sapphires, that won the 2012 Australian Writers’ Guild Award (AWGA) and 11 of the 12 categories of the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Art (AACTA) Awards in 2013. He previously wrote The Sapphires’ Play that won two Helpmann Awards and received sell out seasons at Melbourne Theatre Company and Belvoir, in Sydney.

Wurundjeri wilam – other Aboriginal Writers

First Nation’s writers from across Australia also find a creative place in Narrm and on Wurundjeri Country. MWF[56] provided us with details of First Nations’ women and men currently writing from Wurundjeri Country. In alphabetical order, they are – Evelyn Araluen[57], Susie Anderson[58], Timmah Ball[59], Bridget Caldwell-Bright[60], Maddee Clark[61], Ali Cobby Eckermann[62], Eugenia Flynn[63], Declan Fry[64], Nayuka Gorrie[65], Jeanine Leane[66], Laura LaRosa[67], Jack Latimore[68], Carissa Lee[69] and Neika Lehman[70], Alexis Wright[71]. Gary Foley[72] is also a prolific writer and activist for his People as well as author of several books[73]. We include links to their work.

If you haven’t read their work – get going! If you’ve never heard of them, skill up – listen and learn!

Six leading Australian Universities have a Wurundjeri campus – Melbourne, Monash, RMIT, Victoria, LaTrobe and Swinburne universities. All have programs or degrees in Indigenous studies, history or culture. Many have Indigenous teaches who write extensively.

Indigenous Legal Writers

Whilst not Wurundjeri, we note the work of Indigenous legal writers. Like all lawyers, they are charged with issues of injustice.

Sydney Lawyer and 2011 NAIDOC Person of the Year, Terri Janke, wrote Butterfly Song[74]. It concerns a young law student thrown into her first case concerning ownership of an exquisite and valuable pearl shell. Terri is the author of multiple articles on law as it affects Indigenous Australians, particularly in the field of Indigenous cultural and intellectual property. Terri believes in the power of stories to inspire, connect and heal[75].

Darren Parker and Louise Taylor are two of many other Indigenous lawyer writers. Whilst completing his law PhD at Melbourne University, Parker wrote a two-part series on his personal experience of domestic violence and whether decolonising Australian law will assist Aboriginal People attain justice[76]. Louise wrote on Aboriginal Identity and a Treaty[77].

The peer-reviewed Australian Indigenous Law Journal[78] and the Indigenous Law Bulletin[79] contain multiples contributions on legal matters by Indigenous Australians, both lawyers and non-lawyers. Karen Martin’s excellent book on Aboriginal regulation of outsiders[80], is masterly and provides great advice for non-Indigenous people, particularly researchers.

And, of course, every Australian should have read the Uluru Statement from the Heart[81]. If not, listen to law Professor Megan Davis reading it here:

https://ulurustatement.org/the-statement

Again, we only scratch the surface.

ALWAYS WAS, ALWAYS WILL BE

With Christmas coming, buy their books. Give them as Christmas presents. Take time to read them yourself. They directly link to our continuity as Australians. Gracious, sad, insightful and well informed, this is Australia’s story – told well indeed. We must all celebrate and embrace it.

ALWAYS WAS, ALWAYS WILL BE

KELLEHERS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD

12 NOVEMBER 2020

Download a PDF of this Article HERE

Liability limited by a Scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation

[1] Thomas, William, 1839-1843, The Journal of William Thomas: assistant protector of the Aborigines of Port Phillip & guardian of the Aborigines of Victoria 1839 to 1843, transcribed and annotated by Dr Marguerita Stephens, https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/191430372 accessed 11112020.

[2] Campbell, Alastair (compiler) and Vanderwal, Ron (Ed.), 1999, John Bulmer’s Recollections of Victorian Aboriginal Life 1855-1908, Museum Victoria, Melbourne, Australia.

[3] Mitchell. Thomas, 1839, Three expeditions into the interior of Eastern Australia with descriptions of the recently explored region of Australia Felix and of the present colony of New South Wales, Volumes 1 & 2, T. & W. Boone, London, https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/8486958 accessed 11112020.

[4] For example, Urquhart’s Journals, PROV. VPRS 6/P0, Unit 3, Item 50/73, Hoddle to Urquhart and PROV, VPRS 44/P0, Unit 560, Item 62/11.082, correspondence from Urquhart.

[5] Howitt, A.W., 1996, The Native Tribes of South-East Australia, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra.

[6] For example, Hercus, L.A., Victorian Languages: A Late Survey, Pacific Linguistics, Series B – No 77, Department of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra and Luise A. Hercus, 1992, Wemba Wemba Dictionary, Self published, Canberra.

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patyegarang , accessed 11112020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Dawes_(British_Marines_officer), accessed 10112020 and https://www.sydneybarani.com.au/sites/first-contact/, accessed 10112020.

[8] https://www.bangarra.com.au/productions/patyegarang accessed 11112020.

[9] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-11/patyegarang-and-how-she-preserved-the-gadigal-language/12022646 accessed 11112020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patyegarang accessed 10112020.

[10] Massola, Aldo, 1968, Bunjil’s Cave: Myths, Legends and Superstitions of the Aborigines of South-East Australia, Landsdowne Press, Melbourne.

[11] Chance, Camilla, 2003, Wisdom Man: Banjo Clarke, Penguin Group Australia, Camberwell, Victoria.

[12] https://www.wurundjeri.com.au/our-story/ancestors-past/ accessed 12112020.

[13] For example, Aunty Doreen Garvey-Wandin’s story of durrung of yan-yan (a young man’s heart), https://cv.vic.gov.au/stories/aboriginal-culture/nyernila/woiwurrung-the-durrung-of-the-yan-yan/, accessed 12112020.

[14] Illustration from The Last of the Tasmanians, Woodcut 12 – Walter George Arthur and his wife Maryann the Half-Caste, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/db/Last_of_the_Tasmanians_Woodcut_12_-_Walter_George_Arthur_and_Mary_Anne.jpg, accessed 12112020.

[15] 1839, Colonial Times report, cited by Stevens, op. cit, 63 footnote 97 that cites Morgan, 1986, Aboriginal Education in the Furneaux Islands (1788-1986): A Study of Aboriginal Racial Policy, Curriculum and Teacher/Community Relations, Thesis, Centre for Education, University of Tasmania, 95.

[16] Stevens, Leonie, 2017, ‘Me Write Myself ‘: The Free Aboriginal Inhabitants of Van Dieman’s Land at Wybalenna, Monash University Publishing, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, xxxv.

[17] Brune was a derivative of the name Bruny Island. Per Stevens, op.cit., 9.

[18] Stevens, op.cit., 92, referenced to Brune, 1836, Flinders Island Chronicle, September 10, QVMAG CY825-63.

[19] Stevens, op. cit., 18.

[20] Stevens, op. cit., 63.

[21] Pybus, Cassandra, 2020, Truganini: Journey through the apocalypse, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 197.

[22] For a brief background to Oodgeroo Noonuccal – https://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/noonuccal-oodgeroo-18057 accessed 11112020.

[23] Walker, Kath. 1964, We Are Going: Poems, Jacaranda Press. https://www.jacaranda.com.au/ accessed 11112020.

[24] Image of Oodgeroo Noonuccal, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oodgeroo_Noonuccal, accessed 11112020.

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Davis_(playwright) accessed 10112020.

[26] Davis, Jack, 1983, The First Born and other Poems, J.M.Dent.

[27] Davis, Jack, 1982, Kullark, Currency Press, Sydney.

[28] Davis, Jack, 1986, (reprinted 2012) No Sugar, Currency Press, Sydney.

[29]Burnum Burnum, 1988, Burnum Burnum’s Aboriginal Australia: A Traveller’s Guide, Angus & Robertson Publishers. For further information on Burnum Burnum, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burnum_Burnum accessed 10112020.

[30] Langton, Marcia, 2018, Welcome to Country: A Travel Guide to Indigenous Australia, Hardie Grant Publishing, Richmond.

[31] Bacalja, Alexander, 2020, Australian Literature’s Great Silence, Pursuit, October 20,https:pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/Australian-literature-s-great-silence accessed 27102020, 2.

[32] Bacalja, op.cit., 2-3.

[33] Behrendt, Larissa, 2004, Home, University of Queensland Press, Indooroopilli, Qld, https://www.uqp.com.au/books/home, accessed 12112020.

[34] Lyons Malcolm C. and Ursula Lyons (trans.), 2008, The Arabian Nights, Penguin Classics.

[35] Green, Bill, 2018, Engaging Curriculum: Bridging the Curriculum Theory and English Education Divide, Routledge, New York. https://www.routledge.com/Engaging-Curriculum-Bridging-the-Curriculum-Theory-and-English-Education/Green/p/book/9780367342623

[36] Bacalja, op. cit., 3-4.

[37] Scott, Kim 1999, Benang: From the Heart, Fremantle Press, Freemantle, Australia.

[38] Wright, Alexis, 2006, Carpentaria, Giamondo Publishing, Artamon, Australia.

[39] Winch, Tara June, 2019, The Yield, Penguin Australia Pty Ltd, North Sydney, Australia.

[40] Wright, Alexis, 2017, Tracker, Giamondo Publishing, Artamon, Australia.

[41] Pascoe, Bruce 2019, Young Dark Emu, Magabala Books, Broome, Australia.

[42]Murphy, Aunty Joy and Lisa Kennedy, 2016, Welcome to Country, Black Dog Books, Newtown, NSW – shortlisted for NSW Premier’s Literary Awards and NSW Premier’s History Awards 2017 and winner, Environment Award for Children’s Literature, The Wilderness Society. Murphy, Aunty Joy and Andrew Kelly, Wilam: A Birrurung Story, 2019, Black Dog Books, Newtown, NSW – shortlisted 2020 Childrens’ Book of the Year Award.

[43] Pilkington, Doris 1996, Rabbit Proof Fence, The University of Queensland Press,, St Lucia, Australia.

[44] Poet, Kirli Saunders. Astronomers, Krystal de Napoli and Karlie Noon. Saunders and writer Susie Anderson,

Kirli, 2020, Bindi, Magabala Books, Broome, Australia, Saunders, Kirli,, 2019, Kindred, Magabala Books, Broome, Australia.

De Napoli, Krystal 2020 “Night Sky – The Emu in the Sky,” Life in the Dark, Resurgence & Ecologist, no. 323. Karlie, Noon 2020 “Indigenous Science Can Save Us,” IndigenousX, https://indigenousx.com.au/indigenous-science-can-save-us/, accessed 11112020.

Anderson, Susie, 2015, Three Poems, The Lifted Brow, https://www.theliftedbrow.com/liftedbrow/three-poems-by-susie-anderson accessed 11112020.

[45] Last night’s (11.11.2020) image of the stars – Pleiades, the seven sisters, https://earthsky.org/todays-image/photos-pleiades-seven-sisters, accessed 12112020.

[46] Leane, Jeanine, Other Peoples’ Stories, https://overland.org.au/previous -issue-225/feature-jeanine-leane/ accessed 11112020.

[47] Bacalja, op. cit., 3-4.

[48] https://msd.unimelb.edu.au/indigenous-design-symposium/speakers/mandy-nicholson, accessed 11112020.

[49] Mandy Nicholson, https://www.deadlystory.com/page/culture/my-stories/NAIDOC-week/Mandy_Nicholson, accessed 08112020.

[50] https://www.deadlystory.com/page/culture/my-stories/NAIDOC-week/Mandy_Nicholson accessed 05112020.

[51] Georgia Mae Capocchi-Hunter, https://www.deadlystory.com/page/culture/my-stories/NAIDOC_2019_-_Voice_Truth_Treaty/Georgia_Mae_Capocchi-Hunter, accessed 10112020.

[52] https://www.deadlystory.com/, accessed 10112020.

[53] https://lilkoorigrrrl.wordpress.com/ accessed 11112020.

[54] https://www.deadlystory.com/page/culture/my-stories/NAIDOC_2019_-_Voice_Truth_Treaty/Georgia_Mae_Capocchi-Hunter, accessed 10112020.

[55] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Briggs, accessed 11112020.

[56] KA is proud to support the Indigenous writers’ program with the Melbourne Writers Festival. It is grateful for the leadership of the Board and Rebecca McFarlane in the Festival’s highlighting of Indigenous writers. We also acknowledge the Festival’s co-ordination with this NewsFlash.

[57] https://www.uqp.com.au/books/dropbear

[58] https://www.australianbookreview.com.au/poetry/states-of-poetry/states-of-poetry-new-south-wales/author/5661-susieanderson

[59] http://www.iwpcollections.org/nw2-timmah-ball

[60] https://blakandbright.com.au/artist/bridget-caldwell/

[61] https://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/essay/lifting/

[62] https://giramondopublishing.com/product/inside-my-mother/

[63] https://eugeniaflynn.wordpress.com/

[64] https://meanjin.com.au/blog/never-let-a-crisis-go-to-waste-caring-for-country-and-community-during-a-pandemic/

[65] https://www.google.com.au/books/edition/Growing_Up_Queer_in_Australia/wWiHDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover

[66] https://corditebooks.org.au/products/walk-back-over

[67] https://www.eurekastreet.com.au/article/trickle-down-white-feminism-doesn-t-cut-it

[68] https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/36985859-growing-up-aboriginal-in-australia

[69] https://bookriot.com/author/riss/

[70] https://djedpress.com/2019/09/30/the-moment-neika-lehman/

[71] https://giramondopublishing.com/product/tracker/

[72] https://www.vu.edu.au/contact-us/gary-edward-foley accessed 04112020

[73] Foley, G, Schaap A and Howell E (eds.), 2014, The Aboriginal Tent Embassy: Sovereignty, Black Power, Land Rights and the State, Routledge, London UK, Foley, G and Howell E. (eds), 2015, Pandora’s Box: The Council for Aboriginal Affairs 1967-1976, Keeaira Press, Southport Qld

[74] Janke,, Terri, 2005, Butterfly Song, Penguin eBooks, https://www.penguin.com.au/books/butterfly-song-9781742280004, accessed 10112020.

[75] https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/3410951-butterfly-song, accessed 10112020.

[76] https://blogs.crikey.com.au/croakey/2015/07/17/one-man%E2%80%99s-story-of-surviving-the-trauma-of-family-violence-a-justjustice-longread/ accessed 11112020.

[77] Taylor, Louise, 2003, Who’s Your Mob? – The Politics of Aboriginal Identity and the Implications for a Treaty” Treaty: Let’s get in right, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra.

[78] http://www.ilc.unsw.edu.au/publications/australian-indigenous-law-review, accessed 10112020.

[79] http://www.ilc.unsw.edu.au/publications/indigenous-law-bulletin, accessed 10112020.

[80] Martin, Karen Lillian, 2008, Please knock before you enter: Aboriginal regulation of Outsiders and the implications for researchers, Post Pressed Teneriffe, Qld.

[81] https://ulurustatement.org/ accessed 12112020.

Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation

This fact sheet is intended only to provide a summary and general overview on matters of interest. It does not constitute legal advice. You should always seek legal and other professional advice which takes account of your individual circumstances.

Leave a Reply