NORA BERALDA [1]

Nora Beralda (Bralda) was an Arabunna woman. We acknowledge the honor bestowed on us by her grandson, Reg Dodd, in permitting us to tell her story and include his personal recollections.

Kellehers declares a personal interest in this final NAIDOC Week story. We have, for many years, provided pro bono legal services to the Marree Arabunna People, the direct descendants of Beralda.

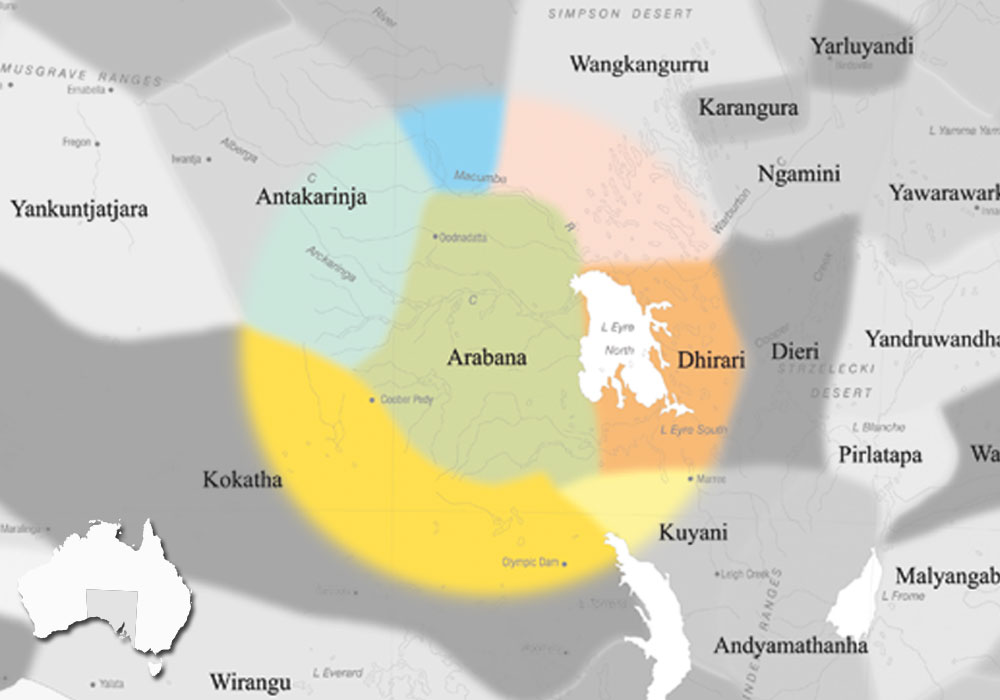

Image 1: The location of Arabunna Country (Horton, 1996)[2]

Arabunna country is desert country: gibber plains with flat top ranges, and low mountains lined along wide horizons. Plants, animals and humans survive in an extreme climate. This is hard country, but deeply beautiful and encaptured by ancient stories. Arabunna People continuously adapted to this environment as it changed dramatically over tens of thousands of years.

Image 2: View of country looking toward Hermit Hill (White, 2007)[3]

A key feature of country is the permanent groundwater from the chain of mound springs stretching around the south edge of Lake Eyre, the southern-most fringe of the subterranean Great Artesian Basin. These springs, particularly where they cluster, are highly significant and sacred Arabunna areas. And before massive draw-down of groundwater for uranium mining at Roxby Downs, these springs would shoot water to a great height. Knowledge of mound spring locations enabled John McDouall Stuart to make the first successful north-south crossing of the Australian continent in 1862.

Fossils on Arabunna country reveal the ancient traces of dinosaurs and a vast inland sea. Rock art there dates back between 5,000 to 10,000 years and is still interpreted today, recording ancient messages for travellers and spirit stories. Beralda’s country includes the original railway line of the now famous Ghan railway, the Oodnadatta Track, the Overland telegraph line, large areas of Lake Eyre, and the edge of the Cooper Pedy opal fields. Established traditional villages remain, hidden from prying eyes.

Like Luggenmener, Turandurey, Kitty and Ballandella, Beralda lived at a time of dramatic white encroachment into her country. In Arabunna country, this occurred some thirty years later than events in Tasmania, Victoria and outback New South Wales. Major changes began with early explorations in the late 1850s and first settlements from the early 1860s.

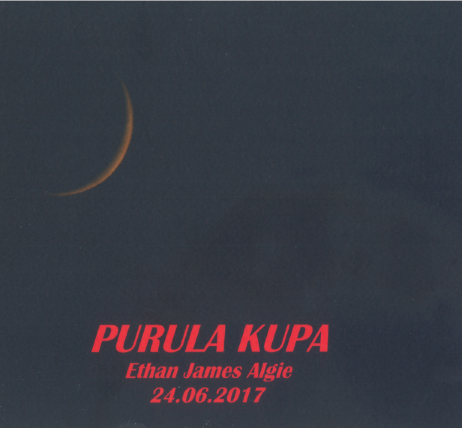

Beralda was a tribal woman of traditional high status among the Arabunna. She had connection to important stories. Mother and daughter were known as Little Moon (Purula Kupa) and Purula Parnda (Big Moon). A treasured image known to Kellehers is the photograph titled Purula Kupa, taken by Beralda’s grandson, Reg Dodd, and presented as a gift to Dr Kelleher’s daughter on the birth of her son at the new moon.

Image 3: “Purula Kupa” , printed photograph taken by Beralda’s grandson, Reg Dodd[4].

Beralda’s entrusted womens’ stories related to thirka, the warm hearth at the fire. At birth, each member of Beralda’s family was placed on the thirka. The thirka story passed, like an heirloom, to Beralda (as the oldest daughter) from her mother (the oldest daughter). In turn, Beralda passed it to her oldest daughter, Reg’s mother who, in turn passed it to Aunty Nancy her eldest daughter, Reg’s sister who died only several years ago, and Aunty Esther[5]. A story such as the thirka story goes back to the beginning of time. It is a creation story about the ancestral being and how the country is made. Ownership of a story like this involves traditional ownership of particular sites and places within the landscape. There can be other custodians, who do not ‘own’ these places as part of their birth-right, but are responsible to look after them on behalf of the traditional owners.

One of Beralda’s stories was about old women travelling and carrying the moon. They travelled for a long time, holding each other’s hands up. Eventually, the moon became too heavy and they became tired. This is a charming story of how the moon sets at the end of each night.

Like poetry, traditional stories carry multiple layers of meaning. For example, another meaning of this story is a commentary on life and death. Its purpose is to show how, eventually, everyone dies. If the woman could have carried the moon forever, they would have lived forever. But, the moon became too heavy for them over time. They eventually collapsed and died. And, from that time, this is what happens to all of us.

These stories have powerful meanings going back thousands of years and, for Arabunna even today, connect them closely with country, having been handed down from generation to generation from Beralda to contemporary descendants.

Beralda was, according to her grandson, Reg Dodd, a very private person. Beralda’s children spoke strongly of the need to speak for country in its own language – as the true test of ownership and connection. They were seeped in traditional language and culture by her influence. Francis Warren, although Australian born[6], was descended from Scottish lineage. He was the seventh son of John Warren (1830-1914), member of the South Australian Legislative Council.

The couple met when Francis came to Arabunna country after his father, John Warren, took up land at a location they called Strangways in 1862. South Australian pastoral leases at this time provided for co-possession of land by Aboriginals and the leaseholder, provided Aboriginals did not interfere with stock or property. John Warren left his son and his brother-in-law, Thomas Hogarth, to run the Strangways property. Later they shifted the head station to Anna Creek and, ultimately, Warren (Senior) and Hogarth developed a pastoral empire that formed part of the Kidman holding, one of the largest pastoral leases in Australia.

It was at Strangways, in ~1862, that Francis first established his relationship with the Arabunna People and met his future wife. He began to learn the Arabunna language. Strangways was a place of special significance to Beralda and her People, with interconnecting mythological stories. It was a traditional gathering place, being fulsome with water and bush tucker. The area was a hub where people moved through, passing on knowledge and skills across locations and generations.

Beralda and Francis went on to have seven children. Their long-term, loving and committed relationship was highly unusual, particularly at a time when many Aboriginal women were so often exploited and abandoned. Our NAIDOC stories of Luggenmener and Ballandella provide sad examples. White men tended to keep relationships with Aboriginal women secret and rarely acknowledged their Aboriginal children or committed to them as their family. It also suggests that unique extended families stood behind the couple. The elite colonial Warren, and the Arabunna elders both agreed to marriages outside tradition, in Beralda’s case a woman of high status marrying well outside traditional Arabunna marriage laws. It also possibly speaks to the status enjoyed by the Warren family in shielding the young family from political or community attack. The Warren family were advocates for Aboriginals, with John Warren speaking in Parliament against the proposed removal of Aboriginal people from their lands in north Australia, then part of the colony of South Australia and, in 1911, against the removal of Aboriginal children from their families.

From Francis’ first arrival on Arabunna country, the Arabunna People supported him and his family’s pastoral operations. In turn, Warren accepted advice from Arabunna Elders as to maintenance and protection of special sites.

The couple initially lived at Anna Creek Station, at the heart of Arabunna country. However, Warren sold his share in this Station to provide funds to establish a homestead for his own family. A 1906 report by the Protector of Aborigines stated:

“All the natives here are a quiet well-behaved lot, and as they are well cared for and looked after by Messrs Hogarth & Warren, they are very contented, and would not be benefited by removal to mission station or otherwise.”

In 1918, the family moved south and created a homestead at the foot of Hermit Hill. The location abutted highly sacred traditional country and comprised buildings constructed previously by white arrivals who lacked understanding of traditional culture and sacred locations. Warren wanted to progress further south to buy Beltana Station but Beralda refused to go off her country.

Due to Beralda’s urging and discomfort at this location, the family moved four years later to their permanent home.

Located a little south-west from Hermit Hill, the new leaseholding was initially called ‘New Well’ in celebration of a 30m well sunk just prior to the move to provide a permanent water source. The location is known now as the Finniss Mission Station (‘Finniss’), a location beloved by all Arabunna. It was situated on significant trade routes running north-south and east-west. The homestead house always maintained a special room allocated for meeting travelling Elders. Beralda’s station became a hub where Aboriginals from other areas began relocating.

Beralda and Francis, not only ensured the safety and protection of their family at Finniss, but also the wider group of Arabunna people. Also, due to their special relationship, they influenced other neighbouring pastoralists to a good relationship with the Aboriginal people who camped on their places.

Beralda enjoyed great respect at Finniss. People looked up to her and she was a cornerstone of everything that happened there. She did not come out bush very often with the other women. She had a strong relationship with Francis, but lived mainly in an Aboriginal ‘village’ area of the station beside the creek. It was here that the community lived traditionally in a series of traditional bush structures positioned along the creek, with each family proximate to one of the many beautiful large red river gums growing in the creek bed. Beralda tended not to live in the main house, although she visited frequently and cared for Francis. Beralda almost always spoke the Arabunna language, using only little English.

Ceremonies and dances were often held in the soft wide dry sandy creekbed among the red gums. The creek wound through country and linked to the sacred Hermit Hill area some distance away. The young Finniss men began their initiation journeys from along the creek. The culture passed on, as the younger ones watched the old people dance the traditional dances and sing the traditional songs. They heard the things that were said. The older people, which eventually came to include Beralda, had a responsibility to pass that knowledge on to the younger ones. The children would watch the dance and then be required to do part of the dance themselves.

Image 4: Deep Creek at Finniss (Moore, 2010)[7].

Beralda’s children were named after Warren’s family who visited from time to time. Warren’s mother was very supportive and visits were made to Adelaide by Francis on business or for horse-racing. Arabunna people would sometimes stay with Justice Hogarth, Francis’ nephew.

Beralda and Francis refused to allow their children or, in time, their grandchildren, to be taken away. They were keen for education but reluctant to involve any church in Finniss fearing unwanted interference and control. Approached by the United Aborigines’ Mission in 1937, they refused. However, in 1939, they finally relented in order to establish a school, medical clinic and, ultimately a kindergarten and workshop training facilities at Finniss. The building bricks for these projects were made by the Arabunna at the station and construction was done entirely by them. The station constructed an airfield and became a Royal Flying Doctor base.

Beralda took sick at Finniss in the 1940s and was flown for urgent medical assistance the long distance south to Hawker on Adnyamathanha country in the foothills at the northern end of the Flinders Ranges. Sadly, she died there and was laid to rest off her country in the Hawker cemetery. Francis lived longer, remaining on Finniss. On his death, in 1958, he was buried in the small cemetery at the Station. By his Will, he specifically bequeathed the Station lease entirely to his and Beralda’s children. The Arabunna people continue their occupation and leaseholding of the Station, currently through the Native Title corporation.

Reg records that although Beralda’s children and grandchildren grew up in a very isolated area seeing few white people, they could head out from that upbringing with confidence in their ability to succeed in the wider world. It was a quiet confidence gained through strong traditional cultural learning and knowledge, together with a mix of skills and attitudes learnt through their family situation at Finniss. It was a deeply nurturing environment.

Reg Dodd believes that what happened at Finniss is quite unique and it flows on from that early time with Beralda and Francis when it was first set up.

“It’s a history we can all be proud of, whether we’re blackfellas or whitefellas.”

Kellehers celebrates this beloved Australian Aboriginal woman.

Her role was unique in forging a peaceful and loving transition for her People on country after arrival of the whitefella. She staunchly retained and transmitted her ancient cultural traditions, alongside partnering a highly significant pastoral station. Like other Aboriginal women, she is largely unknown, unheralded and virtually invisible beyond her descendants. Yet the knowledge she passed, and the influence she exerted on the location and nature of the new settlement in her country, was and is still immeasurable. The sheer fact that she was, through her husband, the owner of an outback cattle station is astonishing. Her role, ensuring that her homestead was a place of respect and harmony for the families living and resorting there, was quiet but immense. She and her husband played a significant role in developing strategies to protect their children and grandchildren from government forceable removable policies and this is also unique within Australia. The establishment of their own Mission to avoid these policies was inspired. Their Station paid fair wages, issued bank accounts and provided education, employment and health services. Aboriginal People at her Station were all treated with immense love and respect. They were encouraged to live an active traditional cultural lifestyle, but still engaged with western education and employment opportunities. Their property was a model of positive and effective ‘transition’ from traditional lifestyle to more modern ways. Hers is a great love story.

BECAUSE OF HER, WE CAN!

***

Update

12 May 2024

At the request of family, we mark with sadness the passing of Kevin Buzacott in late 2023.

It was Uncle Kevin’s lifelong calling to express the voice of his his people, country and deep culture.

His Life Journey is now connected to his Spiritual Journey.

***

[1] Today’s story draws on extensive personal discussions between Dr Kelleher, our principal, and Arabunna Elder, Reg Dodd. It also references the following ‘whitefella’ documents: Malcolm McKinnon’s draft manuscript, provided personally by Mr. McKinnon to Dr. Kelleher (now accepted for publication by Queensland University Press) Talking Sideways at Finniss Springs, rev. June 2017; Dr. M. Moore and Dr. L. Kelleher, Submission in Support of Application for Registration on the National Heritage List, Figure 19a (LAMP, 2010); also, for verification, see ‘Place Details: Finniss Springs Mission and Pastoral Station’ Australian Heritage Database (Register of the National Estate, 2003) https://preview.tinyurl.com/ydh3xz9n.

[2] David R. Horton, Indigenous Language Map (Aboriginal Studies Press, AIATSIS, Auslig, SKM, 1996).

[3] ‘View of country looking toward Hermit Hill’ (David White, 2007) in Dr. M. Moore and Dr. L. Kelleher, Submission in Support of Application for Registration on the National Heritage List (LAMP, 2010), Figure 19a.

[4] ‘Purula Kupa’, printed photograph, taken by Reg Dodd (Beralda’s grandson) and presented as a gift to Dr. Kelleher’s daughter on the birth of her son at the new moon, 2017.

[5] Draft manuscript, Reg Dodd and Malcolm McKinnon, provided personally by Mr. McKinnon to Dr. Kelleher (now accepted for publication by Queensland University Press) Talking Sideways at Finniss Springs, rev. June 2017.

[6] Francis Dunbar Warren was born at ‘Springfield’, his family property at Mt Crawford near Adelaide.

[7] Above, n3, Figure 26.

Leave a Reply