TURANDUREY – explorer[1]

Turandurey came into the story on Wiradjuri country. Her native language was Mathimathi (the Muthi Muthi/ MadiMadi People), but she knew Yitayita and Wiradjuri. Wiradjuri and Muthi country are shown in the maps in Tables 1 below:

Table 1: Map show ing Wiradjuri, Yitayita and MutiMuti language areas[2]

The Wiradjuri peoples are located in central New South Wales on the plains running north and south to the west of the Blue Mountains. The Madi people are located in the Northern Riverina and Far West regions of New South Wales

Mitchell’s party first ‘met’ Turandurey when they, apparently, came into her family camp looking for water. It was on 2 May 1836 at a location ~ halfway between Hillston and Booligal in New South Wales. The family at the camp all fled, except a little girl who stayed with an older blind boy. The little girl was Turandurey’s daughter, Ballandella, then aged ~four. Turandurey was a widow aged ~ 30 years.

After Mitchell asked an old man at the camp to guide the party, Turandurey agreed to accompany the party, prompted by the old man. She knew the country well and was an excellent guide. She readily found water and conversed freely with the Aborigines on the lower reaches of the Lachlan River[3]. She remembered Oxley travelling through country 19 years earlier and also Sturt.

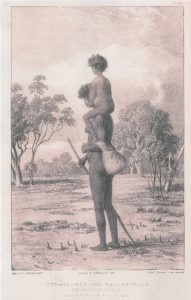

On 5 May 1836, she joined the expedition, with her the little girl. Image 1, by Mitchell who was an excellent artist, shows her lithe and confident in her body in its intimacy with her daughter. Her upper left arm has her traditional scar markings and holds a filled bag, with her hand resting on a rounded tummy. A long stick is in her right hand. She has a gentle face diverted from the viewer’s gaze. The daughter rests tall across her shoulders, her head far above her mother’s, but her hands resting in Turandurey’s hair. The mother and daughter stand central, strongly vertical, within their country. Turandurey’s bare feet softly rest on the earth.

Image 1: Turandurey and Ballendella (Scenery of the Lachlan), Mitchell[4]

Mitchell recorded her as a ‘woman of good sense’[5]. She had talent for entertaining and impersonating Mitchell’s surveying and artistic activities:

“… the widow could also amuse the men occasionally – by enacting their leader, taking angles, drawing from nature, &c.[6]”

Within days of joining the journey, Turandurey became the channel of communication with local Aboriginals. The Aboriginal men in the expedition party were required by cultural law to remain patient and silent, but could each speak alternatively to her in low voices[7].

On 12th May 1836, the party reached the Murrumbidgee River and cooeed across. When the people of the other side emerged, Turandurey:

‘stood boldly forward and addressed the men opposite her in a very animated and apparently eloquent manner’[8].

Again, Turandurey spoke to the Murrumbidgee dwellers who requested that the wild animals in the expedition (the sheep and horses) be driven away – and they were. Mitchell noted the confident authority with which she spoke and that the Murrumbidgee warriors wished to show off to her. He regarded himself as very fortunate to have her skills.

A few weeks later, on 21 May 1836, Ballandella slipped from the expedition cart and, falling under one of the draywheels, broke her thigh in two places. Mitchell found Turandurey:

“in great distress, prostrate in the dust, with her head [sic] under the limb of the unfortunate child”[9].

The expedition’s assistant surveyor, Granville Stapylton, recorded Turandurey showing ‘true concern’ for her child and:

“her language of endearment and soothing is peculiarly soft and musical.”[10].

Turandurey took unremitting care of her daughter but, when the splints were adjusted, the child’s foot was out of its proper position, suggesting that Ballandella walked with a limp for the remainder of her life.

As they moved far beyond Turandurey’s tribal boundaries, she began to yearn for home. On 13 June 1836, they crossed the Murray River, taking all day to get the wagons, carts, stores and stock across. Then they camped for a couple of days. Turandurey’s homesickness continued.

On 1 July 1836, mother and child, with the other woman on the expedition (see NAIDOC Day Four), silently disappeared during a severe frost, when it was almost impossible to track them. Ballandella was brought back the next evening, but Turandurey remained where she camped. So severe were the conditions, that she returned the next morning with her feet severely frost bitten. Despite this, the party made its difficult crossing of the Lachlan River that day.

At this point, the records show pressure on Turandurey to separate from her little girl. The notion of a social/scientific experiment is patent, together with the attraction of early settlers to taking an Aboriginal child in their control. Mitchell writes:

“I intended to put her on a more direct and safe way home after we should pass the head of the Murrumbidgee on our return. I could not detain her any longer than she wishes… [She] seemed uneasy under an apprehension, that I wanted to deprive her of this child. I certainly had always been willing to take back with me to Sydney an aboriginal child, with the intention of ascertaining what might be the effect of education upon one of that race. This little savage, who at first would prefer a snake or lizard to a piece of bread, had become so civilised at length, as to prefer bread; and it (sic) began to cry bitterly on leaving us.”

The reference to the little girl as “IT” is cringe-worthy and shocking.

Before Turandurey’s planned return home, Mitchell gave her shirts, flour, meat and a tomahawk to cut bark for a little canoe that, by swimming, she could use to push Ballandella across the Murray (Millewa) River. The mother and child left, spending two nights in rainy weather unable to light a fire due to hostile Aboriginals on the north side of the Murray. In the end, with her feet still unfit to travel, she crawled fifteen miles back to the expedition party on her hands and knees, her precious child clinging to her back[11].

Difficulties remained ever present for Turandurey. Shortly after their return, two male Aboriginals tried to decoy her from the camp but were foiled when Turandurey gave the alarm. Four days later she fell off the dray, but fortunately sustained no injury.

On 10 August 1836, a few miles north of Casterton, they met a woman with a small boy. Turandurey questioned the woman about the nature of the country, learning that the land to the east was well watered and fertile with firm land for the passage of the carts and drays, so ‘there was not more sticking in the mud’[12].

Leaving Turandurey at a depot near Dunkeld, just south of the Grampian mountains, Mitchell travelled the final south end of the expedition, along the Glenelg River to the sea on 20 August 1836 and Portland shortly after, finding the Henty farming establishment and several groups of whalers on 29 August 1836.

Turandurey and Ballandella sensed Mitchell’s return long before his party appeared:

“(T)heir quick ears seemed sensible of the sound of horses’ feet at an astonishing distance, for in no other way, could the men account for the notice which Turandurey and her child, seated at their own fire, were always the first to give, of my return…”[13].

A week later, on 7 September 1836, the party found a small bower of twigs, the floor of which was hollowed out and filled with dried leaves and feathers. The ground around had been cut smooth, several boughs bent over it and fixed to the ground at both ends. Mitchell recorded that it:

“seemed connected with some mystic ceremony of the aborigines, but which the male natives, who were with us, could not explain”.

Turandurey explained that it was a bower prepared to receive a new-born child.[14]

On the return journey, they met few Aborigines. It was the wet season, the ground was soft and the carts were repeatedly bogged, with the bullocks exhausted. The party split again.

As Mitchell was about to depart, he noticed that Turandurey and Ballandella had their faces marked with white ochre around their eyes. This was a sign of mourning. Turandurey, whom Mitchell recorded as careful and affectionate as any mother could be, had decided to entrust Ballandella’s welfare to Mitchell’s care.

Mitchell’s journal contains the following entry:

“The poor woman, who had cheerfully carried the child on her back, when we offered to carry both on the carts, and who was as careful and affectionate as any mother could be, had at length determined to entrust to me the care of this infant.”

He continues with more problematic thoughts:

“I was gratified with such a proof of the mother’s confidence in us, but I should have been less willing to take charge of her child, had I not been aware of the wretched state of slavery to which native females are doomed. I felt additional interest in this poor child, from the circumstance of her having suffered so much by the accident, that befell her while with our party, and which had not prevented her from now preferring our mode of living so much, that I believe the mother at length despaired of being ever able to initiate her thoroughly in the mysteries of killing and eating snakes, lizards, rats and similar food. The widow had been long enough with us to be sensible, how much more her sex was respected by civilized men than savages, and, as I conceived, it was with such sentiments that she committed her child to my charge…[15]”

Stapylton’s record was a little different:

“the Mother Jin (to me most unaccountably), made a present [of the child] to Mitchell (at least so I am informed)”[16]

Ballandella then left, in September 1836, left with Mitchell and ultimately in October they were on the final road to Sydney[17].

A couple of weeks after Mitchell left for Sydney, the rearguard party reached the Murrumbidgee River. Apparently, Turandurey travelled most of the journey in the cart, possibly because her feet were still not fully healed. However, she is recorded as having grown ‘enormously fat’, with Stapylton seeing fit to record that:

“to the best of my recollection no improp[r[ieties with her as a female have ever taken place”[18].

Upon her return to country, she married ‘King Joey’, Chief of the Murrumbidgee, on 6 November 1836. Stapylton gave her two blankets as a wedding present![19] Apart from the shirts and tomahawk given earlier by Mitchell, this appears to be the complete ‘payment’ to her for her vitally important services to the expedition.

The final passage in Stapylton’s journal reads:

“The Piccaninny is kidnapped away to a station 10 miles distant, with this I have nothing to do [or much to] say nor will I let those who projected the measure & who carried it into execution be responsible to themselves and to the comments of the Public.[20]”

One writer concludes that Turandurey was pregnant and that she may have been pregnant throughout the entire journey and, by November, at six months. However, as an unmarried woman, in a party largely of men, other possibilities exist.[21]

Ballandella continued with Mitchell as part of his household[22] with his family and sent to school.

Turandurey’s fortunes after her amazing expedition and journey are unknown.

Kellehers celebrates this amazing Australian Aboriginal woman – adventurer, linguist, guide and diplomat. It also acknowledges her role as a mother and wife. Her contribution to Australian culture is untold but extraordinary. She is a genuine heroine of the Mitchell expedition.

Be cause of her, we can!

[1] Today’s story relies largely upon the journals required to be kept by the surveyors under legislation regulating the conduct of surveys. Mitchell, T.L., 1839, Three expeditions into the interior of Eastern Australia with descriptions of the recently explored region of Australia Felix and of the present colony of New South Wales, 2 volumes, (2nd ed.), London; Stapylton, G.W.C., 1836-7, Stapylton’s Journal of Mitchell’s Expedition, mss Mitchell Library, Sydney.

Other ‘whitefella’ documents, often drawing on these journals, include good reviews and analysis, for example, E.J.Alan, 1986,Ed. Stapylton: with Major Mitchell’s Au

stralia Felix Expedition, 1836, largely drawn from the journal of Granville William Chetwynd Stapylton, Hobart; Jack Brook, 1988, The Widow and The Child, Aboriginal History 1988, 12:1, 63-78; D.W.A. Baker, John Piper, 1993, ‘Conqueror of the Interior’, Aboriginal History 1993, 17:1, 17-37.

[2] Museums & Galleries of NSW website https://mgnsw.org.au/sector/aboriginal/aboriginal-language-map/

[3] Mitchell, T., 1839, 60-4, Baker, D.W.A, 1993, John Piper, ‘Conqueror of the Interior’, Aboriginal History 1993, 17:1, 20.

[4] Mitchells Journal, op cit., 33; showing on National Museum of Australia website,

http://www.nma.gov.au/encounters_education/community/inland_nsw (accessed 11 July 2018)

[5] Mitchell, 1839, II, 165.

[6] Mitchell, 1839, 27 September 1836, 277.

[7] Baker, D.W.A, 1993, John Piper, ‘Conqueror of the Interior’, Aboriginal History 1993, 17:1, 20-21.

[8] Ibid., 21.

[9] Brook, Jack, 1988, The Widow and The Child, Aboriginal History 1988, 12:1, 65.

[10] Stapylton, 23 May, in Andrews, 1986, 74. Also, Mitchell, T, 1839, 86-7.

[11] Stapylton in Andrews, 1986, 127; Mitchell, T, 1839, II, 165-6.

[12] Mitchell, T, 1839, 31.

[13] Mitchell, ibid., 32; Mitchell, 1839, II, 244.

[14] Mitchell, 1839, II, 251.

[15] Mitchell, 1839, II, 265-6.

[16] Stapylton 1986, in Andrews, 187.

[17] Mitchell, 1839, 86.

[18] Stapylton, in Andrews, 1986, 23.

[19] Stapylton 1986, 235-6.

[20] Stapylton in Andrews, 1986, 235.

[21] Brook, Jack, 1988, The Widow and The Child, Aboriginal History 1988, 12:1.

[22] Bryant, David, 2014, Tocabil Station and its history, News from Rural Funds Management Ltd, November, 2-6, at 4.

Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation

This fact sheet is intended only to provide a summary and general overview on matters of interest. It does not constitute legal advice. You should always seek legal and other professional advice which takes account of your individual circumstances.

Leave a Reply